Confession Number One: I have a bit of a calendar fetish — love wall calendars, but particularly adore those page-a-day calendars. One of my 2023 calendars is called “Outdoor Planet.” It’s full of informational tidbits regarding various explorers, adventurers, sights/trails, and outdoor activities. As I was getting caught up on this week’s pages, I happened across one titled “Outdoor Legends,” regarding Matthew Henson, who was the first person to reach the North Pole.

Confession Number Two: I had not heard of Matthew Henson before, but his name jumped out at me immediately, as I’d just read Jennifer Oliver O’Connell’s excellent article regarding Josiah Henson, the inspiration for the titular character in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” After a quick internet search confirmed both were from Charles County, Maryland, I wondered if they might be related — and it seems I’m far from alone in that. There are numerous references to both men, though I’ve not yet tracked down one that definitively sets forth their relationship.

In my digging, I came across this 2021 blog article by Lew Toulmin, Ph.D., FRGS: “Josiah and Matthew Henson and The Explorers Club.” Notes Toulmin:

Last week I described the astounding life of Josiah Henson and the new Montgomery County Parks Museum that has just opened in his honor. This week I will tell you how I got involved in his story, researched his family and possible links to explorer Matthew Alexander Henson, and how all this relates to the famous Explorers Club.

I have always been interested in history and archaeology, so a year ago I started volunteering at the Montgomery County Parks Archaeology Laboratory at Needwood Mansion. There, while cleaning artifacts from the Josiah Henson site, I learned that the long-awaited Josiah Henson Museum would be opening soon. Since I am a Fellow of The Explorers Club and know that explorer Matthew Alexander Henson, co-discoverer of the North Pole, was the first black member of the Club, I asked, “What is the relationship between Josiah Henson and Matthew Alexander Henson?” The answer from Cassandra Michaud and Heather Bouslog, the lead archaeologists on the project, was, “We get that question all the time. Nobody knows!”

…

I worked with James Henson, a famous lawyer and “Living Legend of Alexandria, Virginia” and proved his line back to Matthew Henson. Together we discovered an old family chart with an asserted (but not yet proven) link between Matthew Henson and Josiah, through the previously unknown Paul Henson, the asserted brother of Josiah and the reported father of Lemuel Henson — the proven father of Matthew Henson. So, if proven, Matthew would be the grand-nephew of Josiah. (Covid has hampered further research, and I suspect that only a major family DNA effort will solve this mystery.)

Actress Taraji P. Henson, known for her starring role as Katherine Johnson in the movie “Hidden Figures,” traces her lineage back to both.

According to Hollywood Ancestry:

Matthew was the half-brother of Taraji P. Henson’s great-great grandfather, Joseph Henson. The Henson family hailed from Nanjemoy, a very small village in Maryland south of Washington, D.C. where the Henson family lived for at least three generations.

Matthew Henson was born 8 August 1866 to sharecropper parents Lemuel Henson and Caroline Waters Gaines. Lemuel Henson is Taraji P. Henson’s 3rd great grandfather. He and his family were free people of color before the American Civil War.

If Toulmin’s research is correct, Josiah Henson is the great uncle of both Matthew Henson and Joseph Henson (Taraji Henson’s great-great-grandfather).

My dear friend @mrdannyglover narrated @JaredBrock's documentary Redeeming Uncle Tom, which will premiere on 200+ PBS stations for #BlackHistoryMonth. It's about my incredible ancestor #JosiahHenson!!! Watch the film & discover the book #TheRoadtoDawn at https://t.co/jlrfY2e2rx

— Taraji P. Henson (@tarajiphenson) February 7, 2019

Like Josiah Henson, Matthew Henson led a storied life. Born in Charles County, Maryland, in August of 1866 to Black sharecroppers, Henson was orphaned at a young age.

At the age of 11, Henson left home to find his own way. After working briefly in a restaurant, he walked all the way to Baltimore, Maryland, and found work as a cabin boy on the ship Katie Hines. Its skipper, Captain Childs, took Henson under his wing and saw to his education, which included instruction in the finer points of seamanship. During his time aboard the Katie Hines, he also saw much of the world, traveling to Asia, Africa and Europe.

In 1884 Captain Childs died, and Henson eventually made his way back to Washington, D.C., where he found work as a clerk in a hat shop. It was there that, in 1887, he met Robert Edwin Peary, an explorer and officer in the U.S. Navy Corps of Civil Engineers. Impressed by Henson’s seafaring credentials, Peary hired him as his valet for an upcoming expedition to Nicaragua.

The pair’s travels took them to Greenland in 1891, and again in 1893. That second trip was fraught with peril.

The two-year journey almost ended in tragedy, with Peary’s team on the brink of starvation; members of the team managed to survive by eating all but one of their sled dogs. Despite this perilous trip, the explorers returned to Greenland in 1896 and 1897, to collect three large meteorites they had found during their earlier quests, ultimately selling them to the American Museum of Natural History and using the proceeds to help fund their future expeditions.

Nevertheless, they continued in their endeavors.

Over the next several years, Peary and Henson would make multiple attempts to reach the North Pole. Their 1902 attempt proved tragic, with six Eskimo team members perishing due to a lack of food and supplies. However, they made more progress during their 1905 trip: Backed by President Theodore Roosevelt and armed with a then state-of-the-art vessel that had the ability to cut through ice, the team was able to sail within 175 miles of the North Pole. Melted ice blocking the sea path thwarted the mission’s completion, forcing them to turn back. Around this time, Henson fathered a son, Anauakaq, with an Inuit woman, but back at home in 1906, he married Lucy Ross.

The team’s final attempt to reach the North Pole began in 1908. Henson proved an invaluable team member, building sledges and training others on their handling. Of Henson, expedition member Donald Macmillan once noted, “With years of experience equal to that of Peary himself, he was indispensable.”

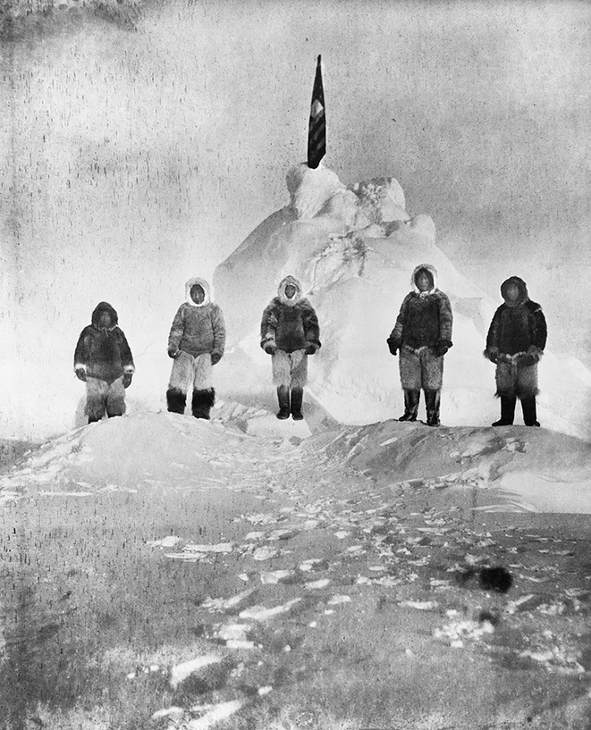

The expedition continued into the following year, and while other team members turned back, Peary and the ever-loyal Henson trudged on. Peary knew that the mission’s success depended on his trusty companion, stating at the time, “Henson must go all the way. I can’t make it there without him.” On April 6, 1909, Peary, Henson, four Eskimos and 40 dogs (the trip had begun with 24 men, 19 sledges and 133 dogs) finally reached the North Pole — or at least they claimed to have.

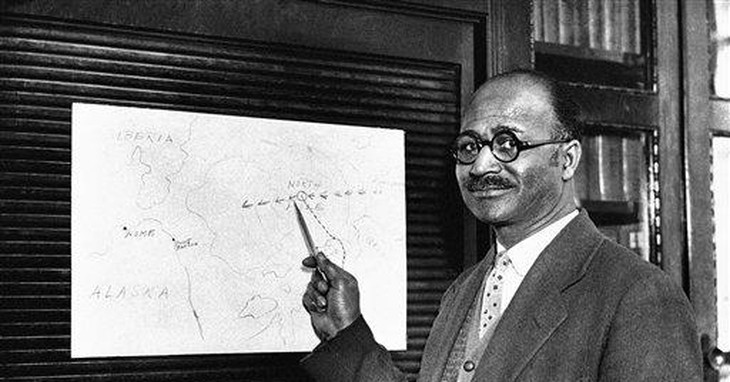

National Geographic provides further details of Peary’s and Henson’s expeditions and the vital role Henson played in their partnership:

Although Peary was the public face of their partnership, Henson was the front man in the field. With his skills as a carpenter and craftsman, Henson personally built and maintained all of the sledges used on their expeditions. He was fluent in the Inuit language and established a rapport with the native people of the region. He was known by all he encountered as “Matthew the Kind One.” Henson learned the methods the Inuit used to survive and travel through the incredibly hostile landscape of the Arctic. “He was more of an Eskimo than some of them.” Peary once said[.]

Henson was a very capable hunter, fisherman, and dog handler. And it was he who trained even the most experienced of Peary’s recruits on each of the eight attempts they made to reach the North Pole.

As alluded to above, the success of that final mission was later called into question.

Unfortunately many doubts were raised to suggest that Peary had also failed to reach the North Pole. Several skeptics speculated that he missed the mark by several hundred miles. With few ways to verify the success of this kind of remote expedition reports of a successful outcome were made on the honor system. Really the only other person to back up Peary’s story was Henson, as the four Inuit hunters didn’t speak English. Though as a black man his testimony was likely deemed by many to be less than credible the strength of his character as substantiated other members of the party carried a great deal of weight in affirming the truth of their journey to the top of the globe.

Further, tensions arose between Peary and Henson as to who should rightly receive credit for being the first. National Geographic explains:

The party had indeed reached the North Pole. But the question remained who had arrived there first. “I was in the lead that had overshot the mark by a couple of miles,” Henson was quoted in a newspaper article upon their return. “We went back then and I could see that my footprints were the first at the spot.”

Upon their return to the United States some reports in the press indicated that there was tension between Peary and Henson as to whom between them deserved credit for reaching the North Pole first. “From the time we knew we were at the Pole, Commander Peary scarcely spoke to me,” Henson would later reveal. “It nearly broke my heart … that he would rise in the morning and slip away on the homeward trail without rapping on the ice for me, as was the established custom.”

It seems odd that after such a long and successful partnership the two men would become estranged from one another. With a difference of a few hours at most it would be reasonable to give Peary and Henson equal credit for having reached the North Pole together as a team. But the racially divisive climate of time would not give an African-American man the same standing in the public eye for the accomplishment of such a monumental feat of human achievement. Peary was the recognized discoverer of the Pole while Henson was relegated to the role of trusty companion. Despite Henson’s indispensable contributions to their efforts for almost 20 years he received very little acknowledgment.

Thus, while Peary was hailed a hero and promoted to Rear Admiral upon their return, Henson, with Roosevelt’s recommendation, became a clerk at the federal customs house in New York City and lived a relatively quiet life, though he recorded the memoirs of his journeys in the 1912 book, “A Negro Explorer at the North Pole.” His biography, “Dark Companion,” written with Bradley Robinson, was published in 1947.

Eventually, Henson’s contributions would be formally recognized. In 1937,

The Explorers Club of New York made him an honorary member. A few years later in 1946 Henson was awarded a medal, identical to the one given to Peary, by U.S. Navy. And in 1954 he was invited to the White House by President Dwight Eisenhower to receive a special commendation for his early work as an explorer on the behalf of the United States of America.

Henson was honored following his death, as well, given a final resting place at Arlington National Cemetery:

Henson died in New York City on March 9, 1955, and was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery. The body of his wife, Lucy, was buried beside him in 1968. In a move to honor Henson, in 1987, President Ronald Reagan approved the transportation of Henson and Lucy’s remains for reinterment at Arlington National Cemetery, per the request of Dr. S. Allen Counter of Harvard University. The national cemetery is also the burial site of Peary and his wife, Josephine.

As noted above, Henson fathered one son, Anauakaq, with an Inuit woman during one of his trips to Greenland.

Henson’s descendants reside in Greenland.

In April 2009, they gathered to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of Henson’s arrival at the North Pole.

Counter and the Hensons arrived in Iqaluit with many items to place in a time capsule: a copy of a book by Counter about Matthew Henson, Henson family photos, letters, and flags from the United States and Greenland.

These were given to a U.S. Navy submarine that planned to deposit the capsule at the North Pole.

Counter also bore a congratulatory letter from U.S. President Barack Obama to take to Qaanaaq.

I’m pleased the serendipitous flip of a calendar page led me on a journey to learn about Matthew Henson, an “outdoor legend.”

Join the conversation as a VIP Member