Legends of the West

We have talked a lot about the history and technology of firearms, and recently some about my own experiences in the use of firearms. But there are some historical figures, as well, who made their way through the world with guns at hand, and we should consider them as well; America’s Old West, after all, is replete with such men.

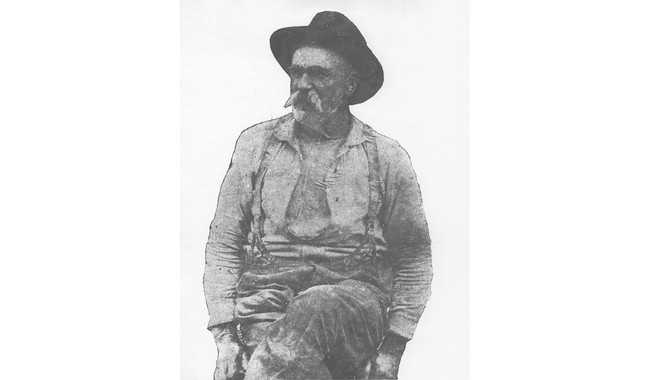

See that handsome, rugged fellow in the photo below? Looks like the very picture of an old-time frontiersman, doesn’t he? Hirsute and tough, yet still ruggedly good-looking despite his age; no doubt a frontier gentleman, a man of good breeding and manners.

Of course, he’s nothing of the sort. This is John Jeremiah Garrison “Liver-Eatin’” Johnston, the indirect inspiration for Robert Redford’s character of Jeremiah Johnson in the movie of the same name. The real Johnston’s story is quite different than the movie version – and a lot more interesting. Johnston was no heroic figure. In today’s world, he probably would have landed in prison. He only narrowly escaped time behind bars in his day. But it’s an interesting contrast between Redford’s noble character and the unsavory, drunken, violent lout on whom Redford’s character was based.

His Origins

His Origins

Johnston was born John Jeremiah Garrison. He emerged into the world in Little York, New Jersey, in 1824, and if anyone could be said to be living proof of the maxim “what doesn’t kill you, makes you stronger”, it is the young Johnston. His father, Isaac Garrison, was a violent, abusive alcoholic who sent his young sons to neighboring farms to labor to pay off his drinking and gambling debts.

It didn’t take long for the young John Jeremiah to tire of this treatment. At age twelve or thirteen – the record is unclear – he signed up to be a crewman aboard a whaler, an occupation he followed until the outbreak of the Mexican War when he signed up with the U.S. Navy.

It was during this tenure that the course of young John Jeremiah’s life changed. He had matured into a massive, intimidating figure; six foot two inches tall, heavily bearded, and two hundred and sixty pounds of solid muscle. His Navy service ended when an officer reprimanded a friend of John Jeremiah’s with the flat of his sword; Garrison knocked the lieutenant arse over teakettle and, facing court-martial, fled ashore. The Navy then, of course, was a harsher place than it is today.

Now he faced a crossroads. Twenty-two years old, with his only skills being sailing and fighting, he decided to head inland, making the obvious choice for youth in his position: To make a living in the Rockies. He adopted the surname “Johnston,” because why not, and struck out for the West.

His Adventurous Career

Johnston surfaced in 1846 in Alder Gulch, Montana Territory, working as a woodcutter supplying the steamboats on that Missouri River port. One apocryphal story of Johnston from around this period describes him lounging on the Missouri River dock with a partner. Johnston was wearing only mule-ear trooper boots and “a filthy red woolen union suit that he had apparently been living and sleeping in for several years.” While he was thus occupied, a riverboat arrived bearing wealthy tourists from St. Louis who were taking in the sights, of which Johnston and his partner were not the least. Several prominent ladies of that city found Johnston and his unnamed partner fascinating and invited him into the steamboat’s parlor for luncheon, with the understanding that he put on some trousers first. Thus more-or-less respectably clad, Johnston and his partner reported aboard the steamer to be feted by the city folk.

Johnston and his partner were nonplussed by the luxurious dining salon, and their confusion was heightened at the end of the meal when dishes of ice cream were passed out.

“John, what is this stuff?” the partner asked.

“Don’t look ignorant,” Johnston told him. “It comes in cans.”

In 1863, he signed up with the Second Colorado Cavalry to serve as a scout. He was with the cavalry for only a few days before going AWOL to spend his enlistment bonus on a drinking binge, but eventually returned to the regiment in time to ride east, where he took part in the battles of Westport and Newtonia. Johnston was shot in the leg but recovered and continued to ride with the Second until his discharge in September 1865.

Related: Biden Still Thinks He Can Win a Civil War

Set at liberty again, Johnston returned to the Montana Territory, where he worked at almost any occupation that would make money: Trapper, fur trader, woodcutter, carpenter, whiskey trader. He viewed the law as only a set of mild suggestions, engaging in running liquor to the various Indian tribes and selling Indian skulls to tourists. In 1868 Johnston formed a partnership with one J.X. Biedler to run liquor to the Indians in an extremely hostile area known as the Whoop Up Territory, which had the reputation of being extremely dangerous for white men; that information bothered Johnston not a jot, and he continued in the illegal whiskey trade until 1873, when he executed an adroit 180-degree turn and got himself appointed as Sheriff in Coulson (now Billings) Montana. Johnston worked as a lawman more or less consistently – again, the record is not complete – until he retired in 1894 at age 70.

Incidentally, there is no record of Johnston’s preferring the Hawken rifle. The movie not only got that wrong, but they also got it badly wrong; a “.30 caliber Hawken gun,” as referenced in the film, would be suitable only for rabbits and squirrels. The only armed photos of Johnston I have found show him with what appears to be a Sharps rifle and, later, an 1876 Winchester.

As to the source of those Indian skulls, that is the part of Johnston’s legend that is best known.

His One-Man War

Legend has it that, in 1847, Johnston took a woman of the Flathead tribe as wife, only to have her killed by a man of the Crow nation; in this respect, the story is much like the one in that movie. But Johnston’s revenge on the Crow was far more brutal than Hollywood’s imaginings.

According to the book Crow Killer: The Saga of Liver-Eating Johnston, taken from the accounts of people who knew Johnston, this one-man vendetta claimed the lives of over three hundred Crow Indians over the course of twenty-five years.

One account has it that Johnston was captured by the Crow. Held prisoner in winter in the northern Rockies, stripped to the waist, tied with thongs, and left in a tepee with a single guard, Johnston managed to work himself free of his bonds. He knocked his guard senseless with a kick, took the brave’s knife, scalped him, and then proceeded to cut off one of his legs. Taking the guard’s leg with him, he fled shirtless into the winter wilderness with only the Indian’s leg for provisions; he lived by this act of cannibalism to reach his partner Del Gue’s cabin, some two hundred miles away.

The appellation “Liver-Eating Johnston” derives from this vendetta, during which Johnston was said to have eaten the livers of the Crow he killed. He may have fostered this reputation, as to the Crow, it was a deadly insult, as they could not go to the afterlife without their livers; but reportedly the incident dates to the early days of the quarter-century conflict when Johnston and several other men fought a Crow war party. Johnston later claimed to have shot an Indian and then ran his knife into the brave to finish him. When he withdrew the knife, there was a bit of liver clinging to the blade. Johnston noticed a young tenderfoot watching, so he pretended to nibble at the liver, then extended it to the young man, asking if he wanted a bite. The tenderfoot, as Johnston put it, proceeded to “sick up his guts” to the amusement of the other members of the party. However, other than this account, there is no actual record of any acts of liver-eating.

Johnston’s taste for revenge (and human legs) ran out in the early 1870s when he formally made peace with the Crow, referring to them thereafter as his brothers. After that, he limited his killing to members of the Sioux and Blackfoot nations.

His Golden Years

Johnston’s health declined after his retirement. His former great strength was eroded by alcoholism, the several wounds he had received in the Civil War, and his years of fighting Indians. He moved into a veteran’s hospital in Los Angeles in 1899 at age 74 and died a year later.

John Jeremiah Garrison Johnston was far more interesting than Redford’s far less colorful depiction. He was a product of his times, as are we all, but even for his times, he was a violent, profane man. A thoroughly unsavory character, he did nevertheless possess determination and great tenacity, traits of which we should all study up on. And again, even for his times, his career of adventuring seems like one big caper across the most dangerous areas of the West, where he fearlessly engaged in the most dangerous occupations around.

We should not overlook the contemptible parts of Johnston’s personality. He was not a man to be respected or held up as a role model. But we shouldn’t overlook his courage and tenacity, either. Maybe, one day, some Hollywood producer will make a movie that more accurately depicts Johnston as he was, one of the toughest, roughest, shootin’est, most colorful characters our nation has ever produced.

Update: This article has been edited for clarity.