In the Beginning, There Were Percussion Caps and Rocket Balls

In the early years of the nineteenth century, there was a lot of innovation in the world of firearms. In my recent series on six-guns, we examined the results of that innovation, but there was of course a lot more happening in other aspects of the gun trade.

All this innovation had its genesis in one thing: The percussion cap.

Before this, all guns used the flintlock mechanism, which evolved from the flint-and-steel snaphaunce locks and the earlier pyrite-and-steel wheellock guns. These guns, apart from the excessively complex Collier revolver, relied on multiple barrels for multiple shots. The early percussion era continued this trend for a few years, until the 1836 invention of the Paterson revolvers by Sam Colt.

See Related: Sunday Gun Day XXIII - The History of the Six-Gun, Part 1

Sunday Gun Day XXIV - The History of the Six-Gun, Part II

The revolver mechanism, however good for sidearms, doesn’t lend itself well to long arms. Why not? Because the cylinder gap in a revolver tends to vent hot gases and, if the gun’s timing is a tad off, spit hot lead shavings. That’s not good on the non-firing arm which, in a normal stance, is positioned near that cylinder gap.

So, the advent of a practical, single-barrel, single-chamber repeating rifle had to wait for the invention of practical fixed ammunition. But that initial fixed ammunition, and the guns that fired it, may not be what you think.

Enter a fellow named Walter Hunt. Hunt, a quick-witted New Yorker who invented such things as the safety pin, the lockstitch sewing machine, the first streetcar bell, and street sweeping machinery, also invented the Rocket Ball self-contained cartridge. Hunt effectively did what gun cranks ever since have been trying to do; he invented a caseless rifle cartridge. The Rocket Ball cartridge was a conical bullet with a hollow base, into which was packed black gunpowder; the whole shebang was sealed with a wax cap with a small hole to allow in a spark for ignition. The Rocket Ball cartridge, combined with a firearm to shoot it, resulted in a real mouse gun, delivering rather less muzzle energy than a modern .25ACP pistol cartridge. It was a practical, self-contained cartridge, though, suitable for feeding from the magazine of a repeating rifle. This was the very thing inventors needed to build the first magazine rifles.

The Rocket Ball was of extremely limited usefulness. Other than being a self-contained cartridge, it really had nothing going for it. It was not powerful enough to hunt anything more robust than a songbird or perhaps an undernourished rabbit. Some professional and even amateur troublemakers were rumored to fear an underpowered gun more than a full-strength piece, as a full-power gun would generally go through and through, resulting in a relatively clean wound; on the other hand, the weaker round would plant a slug in one’s chest, dragging the grease, fouling and (usually dirtying) clothing of the shootee along with it. Bear in mind, this was well before the advent of modern surgery and antibiotics, so the implanted slug and its accompanying junk would stay in place, where the wound would suppurate and fester, often resulting in a very unpleasant death.

By and large, though, the Rocket Ball ammo was pretty much worthless as anything more than proof of concept. The concept it proved, though, was to have long-lasting implications.

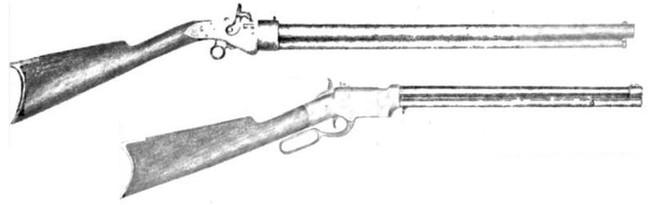

Enter the Jennings

Walter Hunt wasn’t finished. He had his Rocket Ball ammunition; now he needed a rifle to fire it. After some tinkering, he came up with a repeating rifle design that used a tubular magazine under the barrel, with an underlever to lift cartridges into the chamber. As the first Rocket Ball cartridge had no primers, Hunt used an external percussion cap, just like the front-stuffers of the time. After firing, the shooter was required to work the lever to bring a new Rocket Ball into the chamber, place a new cap on the nipple, and then was able to discharge the piece again. This operation, while cumbersome by today’s standards, was still much faster than reloading a muzzle-loading piece.

Hunt lacked funds to develop his “Volitional Repeater,” and so sold his patents to a man named George Arrowsmith. Very little is known about Arrowsmith other than the fact that he had an employee named Lewis Jennings, who slicked up the action of the Volitional Repeater; Hunt then marketed it as the “Jennings Magazine Rifle.”

Probably in large part because of its weak cartridge, the Jennings rifle didn’t blow up a lot of people’s skirts. Only a few prototypes were made, one of which is in the NRA Museum today. Still, it was innovative enough to attract the attention of two gentlemen we’ve met before in our discussions of firearms history.

Remember These Guys?

One of the few customers for the Jennings Magazine Rifle was a fellow named Courtland Palmer, who purchased some Jennings repeaters for his hardware store and, eventually, also purchased the patents to those rifles from Arrowsmith. Palmer had two employees who were keenly interested in seeing this new repeater, and they promptly set about tinkering with the design, resulting in the “Smith-Jennings Repeating Rifle.” In case you haven’t yet guessed, “Smith” was Horace Smith, and the other interested party was Daniel P. Wesson.

Yes, that Smith & Wesson.

Fewer than 2,000 Smith-Jennings rifles were ever made. Those guns command some fancy prices today if you can find one; shooting an original would be out of the question even if ammo were available, and nobody (rightly so) has seen any real reason to build a replica. But Smith & Wesson wasn’t done with the design.

One of the perceived problems with Hunt’s original Rocket Ball cartridge, aside from its rather pathetic power level, was that it wasn’t really a self-contained cartridge. The Jennings and later Smith-Jennings repeaters still required the shooter to affix a percussion cap after levering a fresh round into the chamber. Also, the opening of the Rocket Ball cartridge that let in the spark let in other things, like grease, dirt, and moisture. Smith & Wesson did the obvious; they improved the Rocket Ball by adding a fixed primer at the base of the cartridge.

A new cartridge merits a new rifle.

The redoubtable pair left the employ of Mr. Palmer and set up shop in Norwich Connecticut, originally as “The Smith & Wesson Company” but later, on the addition of a couple of investors, changing in 1855 to “The Volcanic Repeating Arms Company.” The Volcanic rifles and pistols, both using an adaptation of the Smith-Jennings lever action, were the result of that action.

In the Volcanic rifle, the form of the lever-action rifle was finally set: A rifle with a tubular magazine under the barrel, a finger lever that lifted fresh cartridges into the chamber and operated the bolt, and an external hammer. The Volcanic guns were still bound by the limitations of the pathetic Rocket Ball cartridge, but they were quick to load, quick to shoot, had a decent ammo capacity, and used a truly self-contained cartridge, making them the first truly effective mass-produced repeating rifle.

But there just wasn’t a big market for the Volcanic. A traditional percussion-fired muzzle-loader was even more reliable and far, far more powerful. The militaries of the world were still almost universally using front-stuffing muskets and rifle-muskets, partly because they were solid and reliable, partly because they were easier to train poorly educated, conscript soldiers in their use. Mountain men, sport hunters, and pot hunters after big game wouldn’t consider the Volcanic; it was just too weak.

The Volcanic company only lasted a year, closing its doors in 1856 when one of its financial partners finally forced the failing company into insolvency. Once again, Volcanic had produced something that was pretty much worthless except as proof of concept. Once again, the concept they had proved was to have long-lasting implications.

And Then This Happened

And Then This Happened

On the failure of Volcanic, Messrs. Smith & Wesson decamped to purchase Rollin White’s patent and form the “Smith & Wesson Revolver Company,” now enshrined in history and amply described in the last series on the History of The Six-Gun.

Meanwhile, the Volcanic financial partner who administered the mercy shot to the moribund Volcanic company took the remains of that organization to New Haven, Connecticut, renaming it the New Havens Arms Company. That worthy’s name was Oliver Winchester, and in 1857, he hired a plant manager named Tyler Henry. Winchester wanted the Volcanic rifle design upgraded and adapted to the newfangled brass rimfire cartridges that were just then becoming the new, big thing. “Hold my beer,” Henry told Winchester, and the fruit of that business union was to yield great results.

Only three years later, the southern United States grew fractious. Former lever-gun builders Smith & Wesson were not to play a great part in the weaponry supplied for that contest of arms, but Winchester and Henry would prove to play a larger part.

See Related: Sons of Confederate Veterans Lawyer: Arlington's Torn-down Confederate Memorial Not a 'Lost Cause'

No, Not That Henry – the Original Henry

In 1857, Oliver Winchester had taken the remnants of Volcanic to New Haven, Connecticut, where he reformed the manufactory as the New Haven Arms Company. He employed a new design guy, and that designer, Benjamin Tyler Henry, designed a rifle and cartridge that significantly improved on the Volcanic.

First, the cartridge: The copper-cased .44 Henry Flat rimfire cartridge was anemic by today’s standards, firing a 200-grain lead bullet at 1125 fps for a muzzle energy of 570 ft-lbs. But compared to the old Rocket Ball ammo fired by the Jennings and Volcanic repeaters, the .44 Henry was a real powerhouse, roughly the equivalent of the modern .45ACP; here at last was a repeating rifle cartridge with enough power for medium-sized game at close range and even for work against two-legged antagonists.

Second, the rifle: The brass-framed, 1860 Henry retained the better features of the Volcanic, namely, the tubular magazine, the large underlever with separate trigger, the external hammer, and front and rear sights mounted on the barrel, although a tang sight was also available on the Henry. The Henry’s tubular magazine was the first “high capacity” magazine to be mass-produced. Henry rifles were favored by skirmishers, scouts, and cavalry during the War of the Northern Aggression, and many a common soldier saved his pay to buy one, back in those innocent times when a soldier could bring his personal weapon to the fray. A Confederate soldier named John Singleton Mosby famously (and apocryphally) said that the Henry “let the Yankees load up on Sunday and shoot at us all week.”

Some 14,000 rifles were built by the New Haven Arms Company during the war, and a great number of these found their way into the hands of soldiers, who quickly learned the advantage of rate-of-fire. The Rebels managed to get ahold of a handful of Henrys, mostly by capture, but the Confederacy’s arms industry couldn’t scrounge enough copper to replicate any useful amounts of the .44 Henry cartridge. So, the Henry’s advantages were mostly realized by the North, which used it along the Spencer repeaters and various single-shot breechloaders. This was the first en masse use of repeating rifles in a major war.

But the Henry had a weakness. Like the Volcanic before it, the magazine loaded from the front. This meant taking the gun out of commission to top up the load; one had to unshoulder the piece, withdraw the magazine follower and spring, and load new rounds in from the front. The follower was withdrawn by a tab protruding from the magazine tube, which withdrew along an open slot, which allowed dust, dirt, grit, and moisture into the magazine tube. This was a less-than-ideal situation; a better way to load the piece was necessary.

It is one of the greater ironies of the gun world that a company today, calling itself Henry, makes lever guns with a very similar weakness.

The Henry rifle had a successful run, but when the War Between the States finally wrapped up in 1865, a nation looking west was going to need repeating rifles and plenty of ‘em.

The 1866 Winchester

A year after the end of the War of The Northern Aggression, Oliver Winchester was (for reasons I have not been able to determine) in Europe. His employee Henry, apparently disgruntled with his compensation, petitioned to have the Connecticut Legislature seize the New Haven Arms Company and turn it over to him.

Oliver Winchester returned home and put a stop to this early attempt at crony capitalism by reorganizing the New Haven Arms Company into something bigger, better, and Henry-less. He gave this new organization his name, a name that was to be immortal in the annals of American firearms history:

The Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

Thus, a firearms industry legend was born.

As part of the reorganization, Winchester caused the basic Henry rifle to be redesigned. The new rifle, released in 1866, was the first rifle to carry the Winchester name; it differed from the Henry in having a bronze-alloy frame instead of brass, and in loading through a gate in the side of the receiver. This innovation allowed for the addition of a wooden fore-end to make the rifle easier to handle, while making it possible for the magazine tube to be completely sealed against the elements.

In the 1866 Winchester, the final form of the lever-action rifle was complete; a sealed tubular magazine that loaded through a spring-loaded gate in the side of the receiver, a trigger separate from the lever, an external hammer, and sights on the barrel. This pattern would remain the standard until the very last years of the 19th century.

But the 1866 retained the Henry’s .44 rimfire cartridge. Settlers, guntwists and other folks moving West were going to need more power in a repeater. Just a few short years after the introduction of the 1866, Winchester was set to give it to them.

The Gun That Won the West – the 1873

If the year 1873 rings a bell, it’s because we looked at it in the recent series on six-guns. That was the birth year of a true American legend in sidearms, the Colt Single Action Army.

1873 was also the year Winchester released the next iteration of the lever gun, the steel-framed 1873. This rifle used the same toggle-link action as the 1866 Winchester but had a beefier, stronger steel frame. Best of all, it used a new, more powerful centerfire cartridge, the .44 Winchester Center Fire (WCF) later known as the .44-40 Winchester.

Often referred to as the Gun That Won the West, the 1873 was made until 1923 and was later offered in .38 WCF (.38-40) and .32 WCF (.32-20) calibers. Eventually, Winchester reworked the 1866 to fire the newer .44 WCF cartridge, and that rifle sold well until 1899, partly because the bronze-alloy framed 1866 was cheaper than the 1873.

The real genius of the 1873, though, was in its alliance with that famous revolver that was introduced that same year. Colt quickly began building the Single Action Army in .44WCF, calling that version the “Frontier Six-Shooter.” Remington quickly followed by building their 1875 revolver chambered for the .44WCF. Now, a horseman, prospector, lawman, or outdoorsman could carry one cartridge for both rifle and revolver. The system was well-regarded and received enthusiastic endorsements from such folks as William F. Cody. There was even a movie made about the ’73 Winchester, starring Jimmy Stewart and Shelley Winters and co-starring a “One Of One Thousand” special-edition rifle. This set a trend of movies where an actor shares top billing with a rifle, a trend that continued with such films as "Carbine Williams" and "Quigley Down Under."

Today, despite the large number of guns built, original 1866 and 1873 Winchesters command some fancy prices. Fortunately for the hobby shooter, there are several companies making replicas, and some offer varieties not seen in the original guns, like chamberings in the popular .357 and .44 Magnums as well as the venerable old .45 Colt. I’ve handled a couple of these guns and shot one, a Uberti 1873 carbine replica in .45 Colt. They retain the feel of the originals while employing better metallurgy, closer tolerances, and using more powerful ammo.

It was ammo, in fact, that led to the next major innovation to come out of the New Haven works. While the 1873 was solid, reliable, and (for its time) accurate, it still fired a handgun cartridge. The .44 WCF was an order of magnitude more powerful than the .44 Henry Flat it replaced, but the sportsman afield after elk, moose, or bison was still pretty much bound to a single-shot like the Remington Rolling Block and, of course, the Sharps.

So far, no truly successful repeater handling full-power cartridges like the .45-70 was being mass-produced. That left a big, gaping hole in the market. Shooters wanted a repeating rifle with some thump, and Winchester was about to let them have it.

The Centennial – the 1876

Until 1876, the outdoor adventurer faced with two bison would have nothing more to do than look down at his Sharps or Remington single-shot rifle and pick one bison to shoot. But after Winchester introduced the Model 1876, he could shoot both!

The 1876 was an 1873 Winchester writ large, retaining that basic toggle-link design in a bigger, heavier frame capable of handling full-length, full-power rounds. The ‘76 was introduced in the Winchester .45-75 cartridge, loading 75 grains of black powder behind a 500-grain .45 caliber bullet, delivering that thump that shooters were looking for in a repeater. Four versions were offered: the 22” barreled carbine, the 26” Express with a half-length magazine, the 28” Sporting Model, and the 32” Musket.

Not only sportsmen found the ’76 appealing. The Canadian Mounties bought a number of them, as did the Texas Rangers; Geronimo was in possession of a ‘76 when he surrendered to the Army in 1888. The “Centennial” Winchester even caught the eye of a certain young New York whippersnapper named Theodore Roosevelt, who had come west to try his hand at ranching.

The ’76 was popular enough but despite Winchester’s expansion of its loadings to include the .40-60, .45-60, and .50-95 rounds, the ’76’s toggle-link action still wasn’t quite long enough to handle the popular .45-70 Government rounds, meaning that users had to depend on Winchester’s proprietary ammo.

The Centennial represented the last of the first-generation Winchester rifles. The company continued making the ’76 until 1897, but well before that, it was overshadowed by a new generation of Winchesters. This first generation saw its heyday but of late has seen something of a renaissance, as several manufactories have resumed production of the 1866, 1873, and 1876 Winchesters. These new guns, made with modern metals, modern manufacturing techniques, and firing modern ammo, would drive any 19th-century hunter, gunslinger, or cowboy green with envy. It’s a testament to their lasting design that they are still useful on the range and in the field.

Oliver Winchester died in 1880 at 70 years of age. Ownership of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company passed to his son, William Wirt Winchester, who died four months later of tuberculosis. William Winchester’s widow, Sarah Winchester, believed the family was cursed by the spirits of people killed by Winchester rifles, and so moved to San Jose, California, and used her portion of the inheritance and income from the Winchester Repeating Arms Company to open the Winchester Mystery House. This house was intended to confuse and discombobulate those spirits who were (perhaps understandably, if you believe in that sort of thing) peeved at having been sent to their rewards with the products of the New Haven gunmakers. The Winchester House still stands in San Jose; that area is still known for anti-gun sentiment and general kookery of all sorts. It is interesting to reflect that Winchester and Winchester money may have started off the trend of Bay Area lunacy.

Winchester Repeating Arms Company continued humming along, though, and three years after Oliver Winchester’s death, big things were to happen.

And Then This Happened

Winchester had a fair amount of competition from the late 1850s through the late 1890s. In 1860, Christopher Spencer brought out a solid, rugged repeating rifle that used an underlever to operate the gun but was nevertheless very different from the Henry and Winchester offerings. Later, in the mid-1870s, a man named John Marlin entered the gun trade, building an inexpensive pocket revolver, a few shotguns – and lever-action rifles. Marlin’s guns sold for a bit less than Winchester offerings but were good, solid, accurate rifles for their time. A few other makers get involved as well, including classic six-gun maker Colt - but that’s a story for later.

Meanwhile: The folks at Winchester had a plan, a plan that was so clever you could paint it red and call it a fox. As of 1883, they had a brand-new partnership with a certain gun designer out of Ogden, Utah, a fellow named John Moses Browning. That relationship with the Leonardo DaVinci of firearms would prove long and profitable for both parties. Some honest-to-gosh American firearms legends were about to start rolling off Winchester’s lines, and American shooters would be richer for it.

The Other Guys

Every story has some of the Other Guys – the folks who came up with a concept that, while novel and useful, just didn’t quite hang in there. And there are other, Other Guys as well, the ones who keep plugging and manage to carve themselves out a share of the market. In this part of our history of lever guns, we’ll see some of each.

Spencer

The same year Benjamin Tyler Henry came up with the Henry rifle, a Connecticut man named Christopher Spencer came up with another practical repeater, but the Spencer rifle, while operating with a lever under the action, was quite different from the Henry. Spencer completed the design of his signature rifle in 1859, technically beating Henry by a year, but the first commercial release was called the 1860 Spencer.

The Spencer rifle, while technically a lever-action, was very different from the Volcanic, Henry, and Winchester designs. Instead of a tubular magazine under the barrel, the Spencer protected its 7-round tubular magazine by placing it inside the stock, loading through the butt. The action was unusual, in effect a modification to the falling-block breechloaders that were coming into the market at that time. While the offerings of Christian Sharps were single-shots, the Spencer’s magazine fed fresh cartridges into the action while the block was lowered; the process when a shot was fired was to lower the lever, ejecting the empty cartridge; raise the lever, elevating a new cartridge and placing it in the chamber; cocking the big external side-hammer and letting fly.

That was one more action than the Henry required of a shooter, as its bolt cocked the piece’s hammer on its rearward travel. But with various parts of the country fixing to square off at one another, Spencer wasted no time presenting his rifle to the War Department.

There was a problem. The one constant in government is the shortsightedness of bureaucrats, and the War Department in the 1860s was no exception. The Ordnance Department was at that time overseen by Brigadier James Ripley, an old wreck from the War of 1812 with an imagination rather shorter than his nose. He rejected not only the Spencer but any repeater out of hand, insisting that the soldiery would simply waste ammo. At President Lincoln’s insistence, he unbent enough to buy some Sharps breechloaders for the cavalry, but that was as far as he seemed willing to go.

See Related: Ron DeSantis Nails It on Civil War Question, Articulates the Reason the Republican Party Was Founded

Spencer had other plans. (Imagine the consequences if the following events took place today.) On a summer day in 1863, not long after the Federal victory at Gettysburg, Spencer picked up one of his rifles, a hefty supply of ammo, took them to Washington, and proceeded to march with them into the White House, past the inattentive sentries, and into the President’s office to face a startled Abraham Lincoln.

No details remain of the conversation that ensued, but it must have been something along these lines:

Christopher Spencer: “Mr. President, I have a repeating rifle I’d like to show you.”

President Lincoln: “I’d like to see it.”

The following day President Lincoln, Spencer, and Secretary of War Stanton took Spencer’s rifle shooting on the Great Mall(!), following which Lincoln ordered the fossil Ripley to approve the purchase of Spencer repeaters. Ripley largely ignored the order, but a fair number of Spencer rifles found their way into the hands of General Grant’s Army of the West. No less a figure than George Custer became a quick convert to the Spencer rifle, and after the war, many surplus Spencer repeaters were in use all over the country.

The Spencer fared poorly in commercial competition after the war. While the Winchester rifles’ magazines could be topped up with single rounds when the gun was in use, the Spencer required withdrawing the tubular magazine. Also, the Spencer was limited to that company’s own rimfire ammo, while Winchester, only eight years after the war, was hitting home runs in its partnership with Colt on the .44 WCF cartridge.

By this time Spencer’s rifle works were already gone, having closed their doors in 1869 and sold the remainder of their patents and machinery to their competitor, Winchester. In 1882, Spencer tried his hand at gun making again when he started a new company to build what would be the first commercially produced, pump-action shotgun. He continued building that gun until 1889 when the new Spencer Arms Company was sold to Francis Bannerman and Sons of New York, who continued manufacturing Spencer’s shotgun until 1907. But in 1869, his involvement with lever-action repeaters was over.

A year after Spencer struck his tents and bowed out of the lever gun business, a new kid on the block was about to make a big splash. A tool-and-die man from Connecticut who had worked in the Colt plant through the war opened his own company, manufacturing a few single-shot brass derringers, the Ballard-pattern single-shot rifles, and, eventually, some lever guns. That fellow’s name was John Mahlon Marlin. More about him, and more about the history of lever guns, next Sunday Gun Day.