Revolvers B.C.

In the history of six-guns, there are two periods of time to be considered: Before Sam Colt, and after Sam Colt. The Before Colt (B.C.) era was the time of the flintlock, and a surprising number of innovative repeating guns were made during this time, mostly custom jobs and one-offs. But there is one B.C. revolver that stands out, and that is the Collier.

Elisha Collier was a Boston inventor, and his revolver was unique in one respect among flintlock repeating guns: It used a cylinder separate from the barrel to carry the arm’s multiple charges, rather than the pepperbox-styled arrangements that were found before his time. Collier’s first flintlock revolvers were made around 1814 and production continued up to about 1824, all guns being made by John Evans & Sons of London. Estimates of numbers produced vary but are almost certainly under 500 — in both handgun and long gun versions.

The Collier revolver was a fine piece for its day. It was innovative, well-made, well-appointed, and, given the shortcomings of its flintlock ignition system, reliable. One of Collier’s innovations was an automated priming mechanism in the flintlock’s frizzen, that made possible repeated shots without re-priming the pan. But the limitations of the flintlock remained: The guns, like all flintlocks, were vulnerable to wet and wind. The advent of the percussion cap would change all that, but while Collier’s London manufacturer produced a few models using the newfangled percussion ignition system, for the most part, Elisha Collier missed that boat.

The real impact of the Collier revolver was not to come from Britain. It came instead from a young cabin boy aboard the brig Corvo, who saw a Collier revolver on board the ship and set to thinking about revolving repeaters. That cabin boy’s name was Samuel Colt.

The Advent of Colonel Colt

There’s a reason that the saying “God created men, Colonel Colt made them equal” was a truism in the old West. The form of the modern wheelgun was in large part designed and defined by Sam Colt, and with the Colt revolver came the advent of the modern personal sidearm.

The young Samuel Colt was an interesting character. As a youth, he was intrigued by gunpowder, electricity – he made one of if not the first underwater electrically-fired explosive device – and manufacturing. He’s known for pioneering revolver designs but also pioneered mass production and the use of interchangeable parts along with his contemporary, Eli Whitney. He also was among the first to dabble in such modern marketing techniques as celebrity endorsements, soliciting Italy’s King Victor Emmanuel II, among others, to make prominent use of his revolvers. He used art liberally in advertising, paying substantial sums to have artists produce heroic scenes of the West featuring the use of his revolvers in fighting outlaws and Indians. A Renaissance Man he may not have been, but he was a brilliant inventor and marketer, and he changed the nature of sidearms forever.

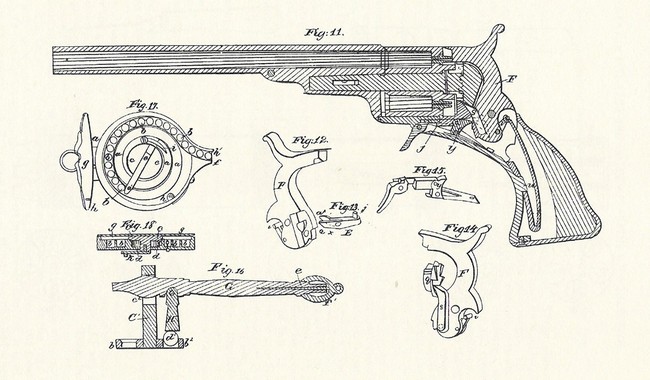

While the Collier revolver may have been the inspiration for Colonel Colt, he had the advantage of the new percussion cap ignition system. After making several prototypes, including the famous hand-carved wooden model he produced while on board the Corvo, he arrived at the configuration that defines the six-gun to this day: a solid frame and a revolving cylinder with stops to align each chamber in turn with the single barrel.

European and American patents in hand, Colt obtained financing and set up shop in Paterson, New Jersey, calling his operation the Patent Arms Manufacturing Company.

The Paterson Colts

Colt’s first revolver venture only ran for six years, from 1836 to 1842. In that time, the company produced 2,350 sidearms, 1,450 revolving rifles and carbines, and 460 revolving shotguns.

The early Paterson revolvers were iconic, innovative, and popular, but, in hindsight, weren’t terribly effective. The lack of a trigger guard is noticeable, the guns having a fragile folding trigger that extended when the hammer was cocked. The first models had to be partially disassembled to be reloaded. But Colt finally achieved a measure of success with the .36 caliber Belt Model #5, commonly known as the Texas Paterson.

By modern standards, the ergonomics of the Paterson revolvers are pretty bad. The odd-shaped grip doesn’t suit people with large hands. The guns were a little light on the barrel end unless you had one of the 9” versions, making them feel whippy in handling; but the long-barreled guns were not as quick to clear leather, putting the horse soldier or gunfighter at a disadvantage. Even so, the gun pointed naturally and shot reasonably well.

By modern standards, the ergonomics of the Paterson revolvers are pretty bad. The odd-shaped grip doesn’t suit people with large hands. The guns were a little light on the barrel end unless you had one of the 9” versions, making them feel whippy in handling; but the long-barreled guns were not as quick to clear leather, putting the horse soldier or gunfighter at a disadvantage. Even so, the gun pointed naturally and shot reasonably well.

The Paterson was imperfect in other ways. Guns made before 1839 were, as noted, difficult to reload, and all the Paterson guns only held five shots.

Being a five-shooter rather than a six-shooter was a problem for one more reason than the one missing shot. All Colt revolvers up to and including the famed Single Action Army had the same issue, namely that the only safe way to carry one was with the hammer down on an empty chamber. This reduced the Paterson to a four-shot gun and (at least, before 1839) one that couldn’t be quickly or easily recharged.

Bear in mind that this was an era in which most sidearms were still front-stuffing single-shots, so the handicap wasn’t seen as being as dire as we might consider it today, in a time where many semi-auto sidearms carry enough ammo in a single magazine to lay low a small army of attackers. Even so, the limitation often led to the conscientious pistolero carrying two or three revolvers on a belt or saddle.

The Patent Arms Manufacturing Company sold a number of sidearms to the US Army, which issued them to troops fighting in the Second Seminole Wars. Those troops favored the Paterson Colt’s capacity, but Army evaluators found the guns too finicky and unreliable in combat, and so disallowed any further purchases. Sam Colt did sell a couple hundred sidearms and a like number of revolving rifles to the Republic of Texas, who issued them to their new-found Navy, but when that Navy disbanded in 1843, the Paterson guns were issued to the Texas Rangers. The Rangers liked the revolving guns, which gave them a much-needed firepower advantage over the Comanche Indians, with whom the Republic of Texas was then engaged in hostilities.

It was the use of Paterson revolvers by the Texans and their increasing popularity with the new waves of settlers crossing the prairies that set the stage for the next step in the development of Colonel Colt’s revolvers. While the Paterson Colt was arguably a failure both in martial and commercial sales and while the Patent Arms Manufacturing Company went under after only six years, a seed had been planted.

That seed sprang forth in 1846, when General Zachary Taylor sent a young Army Captain, Samuel Walker, to Connecticut, where Sam Colt was engaged in manufacturing underwater electrical cable, tinfoil, and marine mines. Captain Walker had one mission: to convince Colonel Colt of the need for a revised revolver, one that would be more reliable, more rugged, and more powerful than the .28 and .36 caliber Patersons. That mission by Captain Walker would bear significant fruit.

The Walker Colt

In 1846, Sam Colt found a young man from Texas knocking at his door. That young man, Captain Samuel Walker, was on a mission: He wanted Sam Colt to return to the business of making revolvers.

As noted, at this time, Colonel Colt was engaged in manufacturing underwater electrical cable, tin foil, and marine mines. Captain Walker wanted revolvers for the newborn Republic of Texas, but he didn’t want a rebirth of the .36 caliber Paterson. He wanted a big, heavy, powerful revolver — a revolver for horsemen. He wanted a dragoon pistol.

Sam Colt was apparently interested because he sat down to create Captain Walker’s desires in steel. The result of this process was the sidearm that first defined the form of the modern six-gun. The 1847 Colt Walker held six loads rather than five, and the big cylinder, while described as a .44, was actually a .45, taking a .457 round or conical ball over as much as 60 grains of FFFG black powder. The gun further had a hinged, attached rammer for reloading and a fixed trigger and trigger guard. This was not only the first modern-form six-gun but also the first magnum revolver, as the big cylinder and the heavy .457 ball packed quite a wallop.

A few years back, I had the pleasure of firing a replica Walker. It was an interesting piece to handle, but sure as hell not a quick-draw piece. The Walker Colt is long, heavy, and cumbersome, but it’s important to remember what the Walker was designed for: It is a dragoon pistol. It was designed for horsemen, to be carried by mounted riflemen (dragoons.) Some Walkers as well as the later dragoon models were adapted to be fitted with shoulder stocks, but making the revolver a carbine presents the same problem that led to the demise of revolving rifles in general: The cylinder gap has a distinct tendency to vent hot gases and, if a gun is ill-timed, to spit the occasional lead shaving. None of this is good for the shooter’s non-firing arm.

The Colt Walker was effective but less than perfect. Poor metallurgy in the early guns led to problems with ruptured cylinders, and the weak loading lever latch often led to the rammer dropping under recoil, jamming the gun up and preventing a fast follow-up shot. In the end, this led to only 1,100 Walker revolvers being built. These problems did, however, lead to the next step in Colt's six-gun development only a year after the advent of the Walker.

The Dragoons

A martial pistol must be powerful, reliable, and tough; the Walker was powerful but fell a bit short on the other two aspects. So, what started with the Walker revolver led to several developments and refinements in the basic dragoon pistol. There were four primary variants of the Dragoon revolvers:

- The First Model Dragoon, made from 1848 to 1850, with oval cylinder stops, a square-backed trigger guard, and no wheel on the hammer where it rode on the mainspring.

- The Second Model Dragoon, made from 1850 to 1851, with rectangular cylinder stops and a square-backed trigger guard. The first few hundred Second Models had the old V-type mainspring and no wheel on the hammer; later guns had the flat mainspring that would persist in Colt revolvers for many decades, along with a wheel on the hammer where it rode on the mainspring.

- The Third Model Dragoon, made from 1851 to 1860, with rectangular cylinder stops and a rounded trigger guard. Colt played around with the Third Model more than the others, producing some with folding leaf sights on the barrel, cuts for shoulder stocks, and so on.

- The 1848 Baby Dragoon, a small .31 caliber pocket revolver. This was later refined into the 1849 Pocket Revolver, which was popular among gold-seekers, gamblers, and outlaws as a hideaway gun.

The various Dragoon pistols were popular, but even the Third Model still weighed in at a tad over four pounds. There was obviously a market for a lighter, handier gun, more along the weight of the old Paterson guns but more modern and reliable. That led to the development of an icon among cap-and-ball six-guns, the Colt Navy.

The Colt Navy Revolvers

My first six-gun was a replica of the 1851 Navy Colt, which is widely regarded as the best-handling six-gun made. I see little reason to doubt that assessment based on my own experience. My Navy had the standard 7 ½” barrel and a brass frame. Back in my youth in Allamakee County, I did a fair amount of fast-draw and reflex shooting practice, drawing and firing from an old drop belt from which the cartridge loops had been removed and a Mexican loop holster. That Colt was excellent for such things, smooth, light, and slick as a snake. I shot it with .380 round lead balls and 30 grains of FFFG in paper cartridges I made myself. I got so I could draw and place six rounds in a regular paper plate at 15 yards very quickly, and with the paper cartridges and a brass capper, I could reload and recap efficiently, usually having the old gun back in action in about a minute. I carried the capper on a string around my neck, paper cartridges in an old tobacco tin, and generally toted the old Navy around with me on many of my adventures in woods and fields.

There was a downside that resulted in my eventually discarding that old six-gun, and that was the brass frame. With every shot, that steel cylinder hammered back into that soft brass frame, eventually deforming the frame to the point where I reckoned the old piece unsafe to shoot. I had a couple of friends who were in a local theater group, so I seated some balls in the empty cylinder, hammered a few balls into the barrel and, removed the nipples to render the gun useless, then gave it to them as a prop gun. I would like to have another of these guns, but when the day comes for me to find another cap and ball gun, it will be a steel-frame version. Brass frame replicas are still common on the gun market as flies in a barn, but I can’t recommend them for the reasons described above.

Back in the day, the Navy Colts were very popular. The well-equipped cowpoke, lawman, or gun twist frequently carried a brace of them in saddle holsters in addition to his belt gun; in the famous Charles Portis book True Grit, in that renowned final charge, it was with a brace of Navy Colts from saddle holsters that Marshal Cogburn engaged the four bad men, not the SAA Colt and ‘92 Winchester wielded by John Wayne in the movie.

Ten years after the first Navy Colts were made, the Colt works brought out the ultimate Navy, that being the streamlined 1861 Navy, also in .36 caliber, with an improved “creeping” loading lever and the added loading clearance introduced in the .44 Army Colt of 1860. There was also a miniature variant, the 1861 Pocket Navy, later refined into the 1862 Pocket Police, both small-framed .31 caliber revolvers.

The Root Sidehammer

The Root Side-hammer Colt, designed by Colt engineer Elisha K. Root, was in some ways a better design than the traditional versions; its solid frame was stouter, and the rear sight was on the frame rather than on the hammer nose. The Root revolver, introduced in 1855, was popular among officers on both sides in the Civil War, but it was a real pipsqueak, manufactured only in .28 and .32 calibers.

The 1860 Army Colt

What many consider the ultimate expression of the Colt cap and ball revolver was introduced in 1860, just in time for the Civil War or, as Mrs. Animal calls it, the War of the Northern Aggression.

In many ways, the 1860 Army combined the best of both worlds. It was a much lighter and handier arm than the Dragoon pistols, and with its .44 caliber loads, packed more punch than the Navy guns. It was a fine, well-crafted, well-balanced piece, handicapped only by its open-topped frame and the odd placement of rear sight on the hammer nose. This was perhaps the ultimate development of the Colt cap-and-ball revolver. Its grip shape was so admirably suited to being fired accurately one-handed, even from horseback, that it carried over to the famous Colt Single Action Army and remains in use on the vast majority of single-action six-guns made today. The use of a rebated cylinder allowed for the use of the same size frame as the Navy revolver's frame and kept the gun’s weight to about two and a half pounds.

As with the Walker and Navy revolvers, it has been my pleasure to handle a few Army Colts, most replicas but notably one original, although we didn’t fire the original. The Army Colt is a pleasure to handle, heavy by modern standards, but the big six-gun points naturally, the barrel rise under recoil is controllable, and the rotation of the curved grip in the hand brings the hammer spur nicely under the thumb, allowing for quick follow-up shots. The .44-round ball or conical bullet in front of 40 grains of FFFG packs a hearty punch. A few shooting sessions with one will bring home exactly why this was probably the most desired martial sidearm of its era.

And the demand for martial sidearms was about to explode.

And Then This Happened

Colt revolvers, especially the 1860 Army but also the Dragoon and Navy types, were soon in great demand as the War Between the States broke out. Sam Colt, having foreseen the great increase in demand, had expanded the factory and, when the southern states began to secede, sold at least 2,000 revolvers to Confederate military buyers, an act which nearly killed the company when the war was over. But what remains inarguable is the reason that the Colt revolvers were in demand by both Union and Confederate armies: They were tough, powerful, reliable sidearms, the state of the art for their day.

Sam Colt passed away in January of 1862, killed, of all things, by complications of gout. The appellation of Colonel was real, Sam Colt having received a commission from the state of Connecticut as commander of the 1st Regiment Colts Revolving Rifles of Connecticut. But that unit never took the field, and Colonel Colt was soon released from service. But the erstwhile Colonel Colt’s company was building thousands and thousands of Army revolvers and a variety of guns for the civilian market, and they didn’t lack for competition. Plenty of people were getting in on the six-gun action, including America’s oldest surviving gunmaker, Remington, as well as plenty of others. Meanwhile, bigger things were afoot; about this time, two men were set to change the world of six-guns forever. Those two men were Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson, and they had an idea and a patent.

Meanwhile, in Ilion, New York

Sam Colt wasn’t the only one out there designing and building great cap-and-ball six-shooters.

In 1816, the son of a small-town blacksmith had built himself a flintlock rifle, which won such acclaim from his neighbors that soon everyone wanted one. Eliphalet Remington responded by going into the gun business. That business grew quickly, and in 1828, Eliphalet (I had to look up how to pronounce that, so I’m going to make you all look it up, too) opened a plant in Ilion, New York. That plant holds a big chunk of American firearms history, as the Remington Arms Company is the oldest surviving incorporated company in the United States, and the Ilion plant, until recently, the oldest manufacturing facility in the country that still produces the same type of product it was built for.

See Related: Remington Arms Company to Close Historic Ilion, NY Operation

But back to six-guns.

In the late 1850s, the aging Remington had working in his plant a gunsmith named Fordyce Beals. (I’m going to make you look up that one, too.) Mr. Beals had in mind a revolver; Remington was agreeable, and the result was the Remington-Beals revolver, commonly known as the 1858 Remington Army revolver. Bear in mind that this was only a few short years after the Remington-Beals revolver hit the market, a group of southern states declared themselves the Confederate States of America, and it was Molly-bar-the-door time. Remington began building revolvers in 1862. The Remington revolvers were made in a variety of frame sizes and calibers from .31 to .44, but the most common is the big .44; over 230,000 guns were made.

In 1862, martial sidearms were suddenly in demand, and Remington produced a good one. The Remington Army revolver, in fact, finalized the form of the modern six-gun as it is today, with a solid frame including a stout top strap with the rear sight firmly fixed thereon. It was a tad heavier than the 1860 Army Colt, but the conscientious horse soldier could carry around a couple of extra cylinders and reload the piece quickly. The Remington had another advantage: Beals was savvy enough to mill slots in the rear of the receiver between the nipple recesses, so one could lower the hammer nose safely into one of these and thus carry the piece safely with all six chambers loaded. This was a first for percussion six-guns, and in wartime, quite possibly a lifesaving one.

The legacy of this fine revolver lives on today. In 1972, the folks at Ruger were thinking of bringing to market a modern cap and ball revolver, built with modern lockwork and manufacturing standards. The result was the outstanding Ruger Old Army, and you can see a lot of the Remington legacy in that piece. Ruger even offers the gun in stainless steel, which is nice when you consider the mess black-powder guns can be to clean; one writer back in the day experimented with his stainless Old Army by shooting a hundred rounds or so, then sticking the gun in the dishwasher. It came out spotless, requiring only a wipe-down and oiling.

But I digress.

The Remington revolver was manufactured from 1862 to 1875, including some versions converted to fire the newfangled brass cartridges. It was replaced by a gun purpose-built for brass cartridges, but we’ll come back to that later.

Other Makers

With Colt’s patent expiring, more folks wanted to get into the revolver business. European manufacturers even got in on the trend, but I’ll try to limit this to American manufacturers for the moment.

Starr

We tend to think of double-action wheelguns as being a more recent thing, usually beginning our mental tabulation with the .38 Colt Lightning and the beefier .41 Colt Thunderer, but at least one double-action six-gun was in use in the Civil War, that being the Starr revolver.

The Starr Arms Company of Yonkers and Binghamton made two variations of their double-action revolver, a .36 caliber piece made in 1859 and 1860 and a .44 caliber gun made in 1862 and 1863. When war broke out, the U.S. government persuaded Starr to produce a cheaper single-action piece, which was made in .44 caliber only from 1863 to 1864, with over 23,000 made and used heavily by Union troops. Plenty of Starrs, especially the earlier double-action models, were used by Confederate officers and cavalrymen as well.

Leech and Rigdon

During the War of the Northern Aggression, the Confederates used mostly imported and Union-made revolvers, with the 1860 Colt in particular seeing a lot of use on both sides. The Confederacy had a few native-built revolvers, but not many. The Leech and Rigdon was one such, and its story is the story of the Confederate armaments industry, which was ended almost before it began.

In 1861, Thomas Leech and Charles Rigdon set up shop in Columbus, Mississippi, to make revolvers. Leech, a cotton factor, provided the capital, while Rigdon, a scale maker with some gunsmithing experience, provided the know-how. The revolver they produced was a near-exact copy of the 1851 Colt Navy, a light, lively .36 caliber piece. They had a contract from Richmond for 1500 revolvers, but it is unclear how many were produced — beginning in late 1862, Leech and Rigdon quite literally produced their revolvers on the run, moving from Columbus first to Selma, Alabama then to Greensboro, Georgia, to evade Federal forces. They gave up on the venture in 1863. Maybe a thousand guns were produced, and they command pretty good prices among Civil War re-enactors and collectors today.

An Oddball – the LeMat

Ever wanted a ten-shooter? If you had such an urge in the late 1850s, the LeMat revolver was your baby. That interesting sidearm had a nine-shot cylinder in either .36 or .42 caliber, which rotated around a 20-gauge shotgun barrel.

Sometimes called the grapeshot revolver, the big piece was originally designed by Jean Alexander Le Mat of New Orleans on or about 1856. A few of these guns, probably less than a hundred, were manufactured in Philadelphia, while the balance, close to 3,000 guns in all, were made in Europe. A fair number were smuggled into the Confederacy during the “Unpleasantness,” where they were much sought-after as cavalry sidearms.

Le Mat had originally hoped to market his revolver to the US Army as a dragoon pistol. A US Army Major named Pierre-Gustave Toutant (P.G.T.) de Beauregard was his advocate to the Ordnance Department (as well as his cousin), but the US Army was not interested. In 1861, after Cousin Pierre-Gustave abandoned the US to serve in the Confederate Army, he secured a contract for 5,000 LeMat revolvers from Richmond. Only about 2,500 made it through Scott’s Anaconda, but the LeMat grapeshot revolver’s place in history was secure; at least one manufacturer makes a replica available today.

The idea of the combination gun, in general, is still popular, such pieces ranging from high-dollar German Drillings to the old Savage 24 over/under, usually mounting a .22 rimfire barrel over a .410 or 20-gauge shotgun. But the combination of a revolver with a shotgun barrel belongs solely to the LeMat.

Then There Were These Guys

Meanwhile, Horace Smith and Daniel B. Wesson weren’t sitting on their hands.

When Sam Colt’s revolver patent expired in 1856, Smith & Wesson were ready, but they had some new ideas. They quickly secured the services of former Colt gunsmith Rollin White, who held the patent on a revolver with bored-through cylinders to take the newfangled brass cartridges. Their first model, called the #1, wasn’t a very effective piece as it was chambered only in .22 short. But it had not only the bored-through cylinder but a hinged frame, with the hinge at the front of the topstrap; this allowed the barrel to swing up and rearward, so the shooter could remove the cylinder to reload.

This was fast and, with the new brass cartridges, handy and clean. The brass cartridges were much less susceptible to moisture and wind than loose powder and ball, and less likely to disintegrate in the pockets or saddlebags than paper cartridges. Smith and Wesson knew they were on to something, and so in 1862, they scaled up their revolver into the #2, chambered for the .32 S&W Rimfire Long cartridge.

Now, the Union troops had something interesting: a light, handy sidearm that reloaded in a hurry. The black powder cartridge still made a mess, and even in .32 caliber, the gun was something of a pipsqueak. But there was a complication: In 1865, peace was breaking out all over, and the market for martial sidearms was about to take a nosedive.

And Then This Happened

But America, now that the “Recent Unpleasantness” had ended, was looking West again, and with that westward movement came the desire for sidearms. Colt was still in the mix but, for the time being, could offer only cap-and-ball guns, unlike their esteemed competition.

Speaking of Smith and Wesson: They had been busy improving on their basic six-gun while all this other stuff was going on. When the War of the Northern Aggression ended, they held that patent that said to the nation that they were the only ones that could manufacture revolvers with bored-through cylinders for metallic cartridges, and they were about to take that idea and run with it. Things in the six-gun world were about to leap forward once again, and the Colt folks were about to face some hard times.

The Cartridge Era Begins

At the end of the Civil War, big changes were coming to the world of six-guns, and those changes were originating in Springfield, Massachusetts. Still, revolver manufacturers, in general, were about to see some busy times – and the state of the art in revolvers was destined to change dramatically over the next forty-odd years.

Come back next week for Part 2, to see what happened as the brass cartridge became universal.