On Thursday, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a Maryland District Court decision which placed a nationwide injunction on Donald Trump’s infamous executive order/“travel ban” (“EO-2”), barring its implementation. The ruling came as a surprise to some, as EO-2 was thought to be a substantial improvement on EO-1 (previously struck down by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals), and the 4th Circuit is considered a more conservative court than the 9th. (Interestingly, the 9th Circuit will also rule on the issue shortly. Oral argument was heard there on May 15th, following the ruling issued by a Hawaiian District Court, but given their previous ruling on EO-1, the odds don’t look to be in Trump’s favor there either.)

In a sharply worded opinion, joined in full by seven judges with three more concurring with the result, Chief Judge Roger Gregory right off the bat signals where the Court is going, by pointedly observing that EO-2, “speaks with vague words of national security, but in context drips with religious intolerance, animus, and discrimination.” As a preliminary matter, the Court held that the Plaintiffs had standing to bring the challenge to EO-2. The Court then considered the proper test to apply to determine whether the Order violates the Constitution. The District Court applied the Lemon test, a standard which courts traditionally use to assess laws challenged under the Establishment Clause. Under Lemon, government action will be deemed to violate the Establishment Clause unless it: 1) Has a significant secular purpose; 2) Does not advance or inhibit religion as its primary effect; and 3) Does not foster excessive entanglement between government and religion.

The government argued that the proper standard was set forth in the 1972 case of Kleindienst v. Mandel, which sets forth a more limited review on immigration matters, granting significant deference to the executive branch in that area. Under Mandel, an order such as EO-2 merely needs to be “facially legitimate and bona fide” to survive a challenge.

The Court of Appeals ultimately applied an amalgam of the two tests, first examining EO-2 under the requirements of Mandel. While the Court agreed that the stated interest of national security meets the “facially legitimate” requirement of Mandel, it zeroed in on numerous statements by Trump advisors and Trump himself to conclude that “national security” was merely a pretext for what amounts to a Muslim ban, and that the government was acting in bad faith by issuing EO-2. This then opened it up to an examination under the more rigorous requirements of Lemon. The Court found that EO-2’s primary purpose was religious – i.e., “to exclude persons from the United States on the basis of their religious beliefs.” Thus, it fails the first prong of the Lemon test, making it likely the Plaintiffs will succeed on the merits of their Establishment Clause claim, and thereby justifying the injunction.

Though the opinion is lengthy (205 pages!), it didn’t take long for legal scholars and pundits to weigh in with their respective takes on it. At the Washington Post, Ilya Somin viewed the decision as “an important victory for opponents of the travel ban.” Somin opines that, “Ultimately, the revised order has most of the same flaws as the original version.”

Over at National Review, David French tears into the 4th Circuit’s ruling, noting that:

“A strange madness is gripping the federal judiciary. It is in the process of crafting a new standard of judicial review, one that does violence to existing precedent, good sense, and even national security for the sake of defeating Donald Trump. We’ll call this new jurisprudence “Trumplaw,” and its latest victim is once again the so-called Trump travel ban. The perpetrator is the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals.”

French chalks the ruling up to a finding that “hurt feelings” trump (no pun intended) “the government’s asserted national-security interest in pausing to reexamine foreign entry from hostile and war-torn countries.” French is highly critical of the Court’s decision to look behind the Order which, on its face, clearly is lawful, to determine “good faith.” He concludes:

“The sad reality is that this takes place in the aftermath of an event — the Manchester bombing — that demonstrates that one of the countries on the list, Libya, is in fact a hotbed of terrorist activity. The bomber traveled to Libya and allegedly had help there. He was a British citizen and not subject to the travel pause, but his journey illustrates the very real dangers of lawless regions gripped by jihad. Is it unconstitutional to pause entry from that nation to make sure that we can properly vet and screen for ISIS sympathizers? The Supreme Court has always said no. Today, the Fourth Circuit says yes. Today, the Fourth Circuit has chosen to distort the law and risk our national security to stop Donald Trump.”

Following the Court’s ruling, Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a statement indicating his intent to appeal the matter: “This Department of Justice will continue to vigorously defend the power and duty of the Executive Branch to protect the people of this country from danger, and will seek review of this case in the United States Supreme Court.” The government has 90 days to file its appeal but is expected to do so sooner.

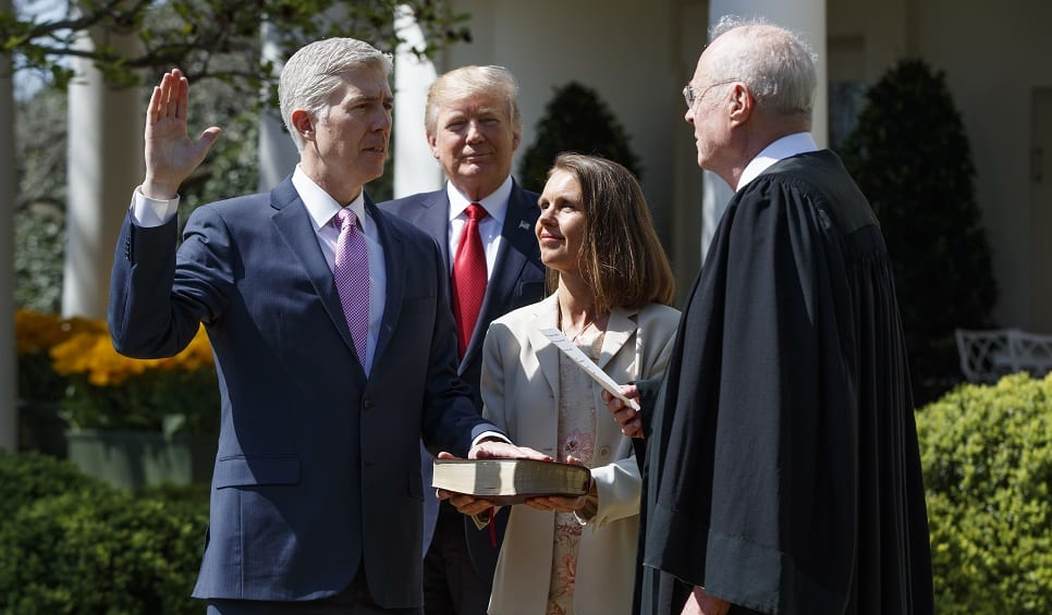

Now all eyes are on the Supreme Court – what will a Court which now includes Neil Gorsuch do with this particular hot potato? I imagine most would consider Kagan, Sotomayor, Ginsburg, and Breyer safe bets to uphold the 4th Circuit’s ruling. Similarly, odds are that Alito, Thomas, and Roberts will rule against it. That leaves Kennedy and Gorsuch.

While Kennedy does sometimes side with the liberal wing of the Court, in my assessment, he will not do so in this arena. His prior rulings point to his inclination to limit the courts’ interference with the executive branch when it comes to immigration matters. For instance, in the 2001 case of Zadvydas v. Davis the majority held that the Attorney General did not have the power to indefinitely detain aliens who were admitted to the United States, but subsequently ordered removed. Though the Court acknowledged the plenary power of the political branches’ over immigration, it maintained that power still “subject to important constitutional limitations.” Kennedy filed a dissent, noting:

“Far from avoiding a constitutional question, the Court’s ruling causes systemic dislocation in the balance of powers, thus raising serious constitutional concerns not just for the cases at hand but for the Court’s own view of its proper authority. Any supposed respect the Court seeks in not reaching the constitutional question is outweighed by the intrusive and erroneous exercise of its own powers. In the guise of judicial restraint the Court ought not to intrude upon the other branches. The constitutional question the statute presents, it must be acknowledged, may be a significant one in some later case; but it ought not to drive us to an incorrect interpretation of the statute. The Court having reached the wrong result for the wrong reason, this respectful dissent is required.”

More recently, in the case of Kerry v. Din, Kennedy concurred with Scalia, Roberts, Thomas, and Alito, who, as the majority, reversed the 9th Circuit holding that the Plaintiff had a protected liberty interest in her marriage that entitled her to a review of the denial of her husband’s visa. Kennedy concluded there was no need to decide whether the Plaintiff had a protected liberty interest, because, even assuming she did, the notice she was given regarding the denial of the visa satisfied the requirements of Due Process. In his concurrence, he cited to the Mandel case cited previously,

“The reasoning and the holding in Mandel control here. That decision was based upon due consideration of the congressional power to make rules for the exclusion of aliens, and the ensuing power to delegate authority to the Attorney General to exercise substantial discretion in that field. Mandel held that an executive officer’s decision denying a visa that burdens a citizen’s own constitutional rights is valid when it is made “on the basis of a facially legitimate and bona fide reason.” Id., at 770. Once this standard is met, “courts will neither look behind the exercise of that discretion, nor test it by balancing its justification against” the constitutional interests of citizens the visa denial might implicate. Ibid. This reasoning has particular force in the area of national security, for which Congress has provided specific statutory directions pertaining to visa applications by noncitizens who seek entry to this country.” (Emphasis added.)

Assuming Kennedy stays true to form, that means Gorsuch will be the key. Will he side with the conservatives on this one? The easy assumption is yes. However, Ilya Shapiro raised an interesting point back in February regarding EO-1, and the irony that Gorsuch would be more likely to oppose it than Merrick Garland would have. Shapiro pointed out that Gorsuch “has led a campaign against judicial over-deference to the executive.” Gorsuch voiced concern about broad deference doctrines in the case of Gutierrez-Brizuela v. Lynch, wherein he stated, “There’s an elephant in the room with us today….But the fact is [broad deference doctrines] permit executive bureaucracies to swallow huge amounts of core judicial and legislative power and concentrate federal power in a way that seems more than a little difficult to square with the Constitution of the framers’ design. Maybe the time has come to face the behemoth.”

However, with regard to EO-2, Shapiro sees it differently:

https://twitter.com/ishapiro/status/868446574346686464

I’m inclined to agree. My hunch is that Gorsuch’s anti-judicial-overreach instincts will hold sway, and the government’s plenary power argument will win the day – because of the specific arena in which this battle is being fought – i.e., immigration.

In the present case the 4th Circuit, seemingly spurred by distaste for Trump, has stretched beyond the Supreme Court’s precedents on immigration matters, using a combination of tests SCOTUS has not previously employed. Anytime a Court is grafting a new test onto an established one, there is a strong indication they’re engaging in judicial activism, and my read of Gorsuch is that he won’t be keen on that approach.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member