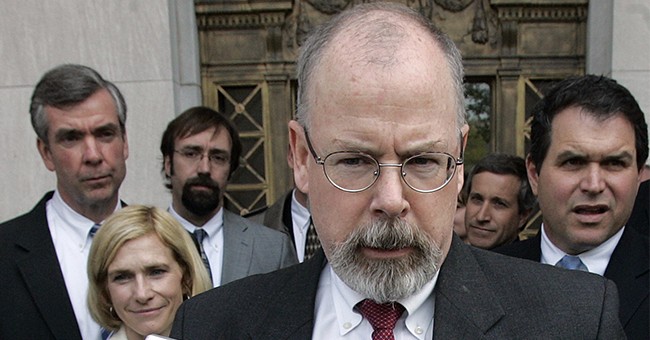

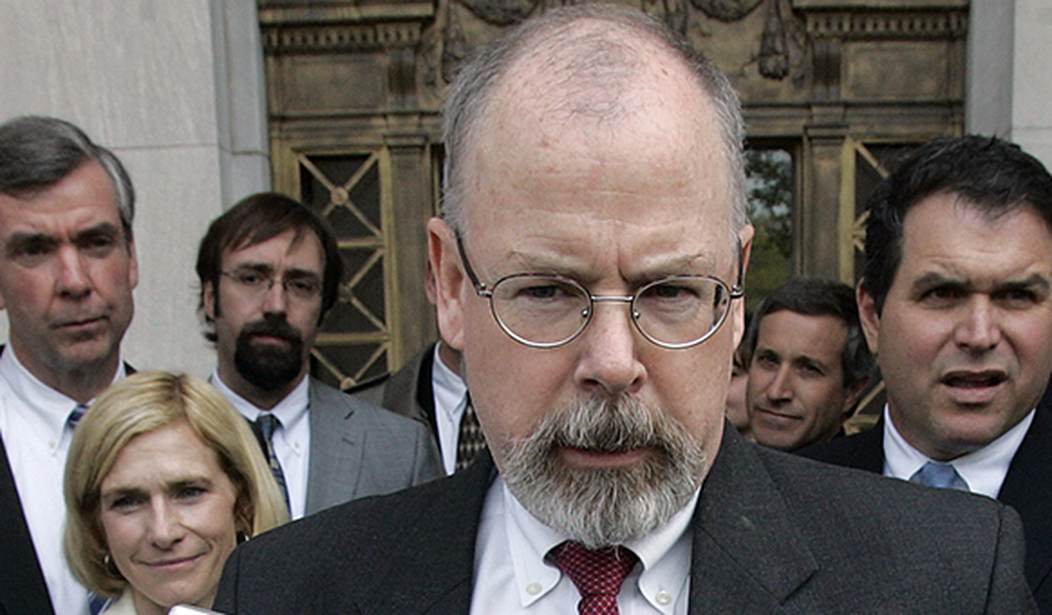

Yesterday I wrote this story about my speculation for the reasons behind the resignation of Durham’s chief deputy. I surmised that she may have led the “filter team” whose job it is in this kind of investigation to go through the investigation conducted by the Inspector General in order to remove all evidence of compelled statements given by federal employees, and any evidence developed by the IG that could have only come from such compelled statements.

In Garrity v. New Jersey, the Supreme Court held that interviews of law enforcement officers done by internal affairs investigators make the statements of the officers “involuntary” if the officer is told at the time of the interview that refusing to answer questions will result in the termination of their employment.

Since “involuntary” statements can’t be used in criminal cases, and evidence derived from such statements are “fruit of the poisonous tree”, a criminal prosecution that comes after an Inspector General’s investigation must be able to establish that no “compelled” statement given by any of the indicted defendants were used to build the case against them.

Along the way yesterday while doing some more reading on the subject, I came across a 2017 decision from the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York — US v. Allen — where the appeals court reversed the convictions of two British bankers for their involvement in a scheme to manipulate the “LIBOR” rate (London Interbank Offer Rate) — an international interest rate that is used by banks all over the world as a benchmark for certain types of transactions, and from which many other interest rates are established. The two defendants had worked at an London Branch of Rabobank, and played a role in that bank’s LIBOR submission process that influenced the setting of the LIBOR rate.

The two bankers were initially investigated by UK banking authorities. In accordance with British law, a refusal to cooperate and answer questions was itself a basis for imprisonment. As a result, both cooperated and gave statements to UK investigators. The UK ultimately charged only one of their Rabobank business associates — a gentleman named Robson — and in making the case against Robson the UK authorities released the compelled statements of the two defendants. Robson reviewed the statements closely, taking extensive notes of the claims made against him by his two business associates.

For reasons which the decision says are not clear from the record of the case, the UK authorities dropped the prosecution of Robson, and the DOJ Fraud Section took up the matter, indicting Robson in the Southern District of New York.

Robson ultimately pled guilty, and himself became a cooperating defendant. He provided a significant amount of information to investigators in the US, and that information was used to secure indictments of the Allen and Conti, the two defendants in the appeal. Robson testified at the trial of Allen and Conti, and the jury convicted them of bank fraud and wire fraud under US law.

There are four attorneys from the DOJ Criminal Division Fraud Section listed on the decision as having been counsel for the government, which strongly suggests it was the Fraud Section that tried the case.

One of the attorneys listed was the Chief of the Fraud Section at the time — Andrew Weissmann.

The Second Circuit reversed the convictions of the two bankers and ordered the charges dismissed.

First, the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition on the use of compelled testimony in American criminal proceedings applies even when a foreign sovereign has compelled the testimony.

Second, when the government makes use of a witness who has had substantial exposure to defendant’s compelled testimony, it is required under Kastigar v. United States , 406 U.S. 441, 92 S.Ct. 1653, 32 L.Ed.2d 212 (1972), to prove, at a minimum, that the witness’s review of the compelled testimony did not shape, alter, or affect the evidence used by the government.

Third, a bare, generalized denial of taint from a witness who has materially altered his or her testimony after being substantially exposed to a defendant’s compelled testimony is insufficient as a matter of law to sustain the prosecution’s burden of proof.

Fourth, in this prosecution, Defendants’ compelled testimony was “used” against them, and this impermissible use before the petit and grand juries was not harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

Weissmann knew this was the law at the time — this is the EXACT basis upon which Oliver North and John Poindexter’s convictions were thrown out after Iran-Contra. North and Poindexter were both subpoenaed to testify before Congress, and both were compelled to testify by a grant of immunity. Had they refused they would have been in Contempt of Congress. After they were convicted at trial by Iran-Contra prosecutor Lawrence Walsh, their convictions were reversed because Walsh could not establish to the satisfaction of the Court that none of Walsh’s witnesses had watched or read North and Poindexter’s compelled testimony in which they admitted to certain conduct that later formed the basis of the criminal charges brought by Walsh. Thus, all Walsh’s evidence at trial was presumed to have been “tainted” by the compelled testimony given by North and Poindexter, and their convictions were thrown out on appeal.

You know who else knows that — a guy named Michael Bromwich, who was one of the prosecutors in the North and Poindexter trials. Bromwich represents Andrew McCabe.

THIS is the reason why Durham must be slow and deliberate. He must be able to show that the evidence relies on in any criminal case is not “tainted” by evidence obtained by the IG’s investigation through compelled testimony.

The Allen case shows you exactly what happens on appeal when those issues are not dealt with and resolved BEFORE an indictment is returned.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member