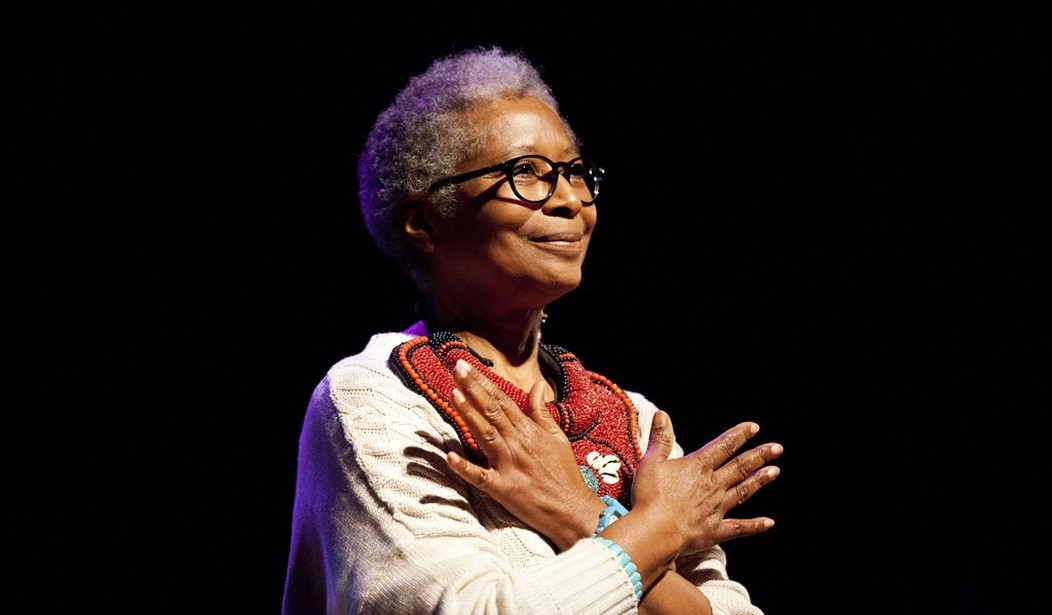

Zora Neale Hurston lived a fabulous and consequential life. It is because of her that we have documented certain Black dialects, lineages, and cultural practices of the South. The writer Zora Neale Hurston experienced a revival of sorts after her death. Thanks to the writer Alice Walker (pictured), Hurston’s consequential works were given fresh life and even greater weight, with two posthumously published works, and a Society and a Trust in her name.

Zora Neale Hurston was an American author, anthropologist, and filmmaker who shed a light on issues facing Black Americans, particularly in the South. She wrote more than 50 plays, stories and essays in her lifetime! #BlackHistoryMonth pic.twitter.com/DPPfXXVqTM

— Rep. Terri A. Sewell (@RepTerriSewell) February 10, 2021

Hurston was an iconoclast who lived a life she chose, not one that she was forced into by her race, circumstances, or geography. Hurston wore the hats of writer, anthropologist, and folklorist with ease and aplomb, and worked to depict Black life in the South and in Caribbean countries in full splendor, without apology.

“Throughout her life, Hurston, dedicated herself to promoting and studying black culture. She traveled to both Haiti and Jamaica to study the religions of the African diaspora. Her findings were also included in several newspapers throughout the United States.”

What I most love about Hurston is that she navigated a number of worlds, but unlike many writers of her time, she never exhibited shame in the world from which she came, nor did she seek to escape its bonds. It is this comfort and acceptance that allowed her to write about the Black South as she did, and her important work of documenting all of its unique characters and nuances.

Zora Neale Hurston was born on January 7, 1891 in Notasulga, Alabama, to John Hurston, a carpenter and Baptist preacher, and Lucy Potts Hurston, a former schoolteacher. Hurston was the fifth of eight children, and when she was three, the family moved to Eatonville, Florida where Hurston spent her formative years. This time would shape her world view. Her father was even one of the first mayors of the town.

Valerie Boyd notes on the official Zora Neale Hurston website:

“In Eatonville, Zora was never indoctrinated in inferiority, and she could see the evidence of black achievement all around her. She could look to town hall and see black men, including her father, John Hurston, formulating the laws that governed Eatonville. She could look to the Sunday Schools of the town’s two churches and see black women, including her mother, Lucy Potts Hurston, directing the Christian curricula. She could look to the porch of the village store and see black men and women passing worlds through their mouths in the form of colorful, engaging stories.”

Hurston did not seek her validity or identity from so-called white society. She followed her muse, and did what she needed to do to live the life she envisioned for herself.

One of my favorite Hurston quotes, she said,

“Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It’s beyond me.”

According to writings and pictures, her company was very fun and pleasurable.

Hurston’s mother was the driving force behind her adventurous spirit. Lucy Potts Hurston encouraged her children, to “jump at de sun.” Hurston wrote, “We might not land on the sun, but at least we would get off the ground.”

Sadly, Hurston’s mother died when she was 13, and her father remarried and pretty much neglected and forgot about his children. Hurston was on her own, and began to live a nomadic life. Hurston worked a series of menial jobs while attempting to finish her schooling. According to the website, she joined a Gilbert & Sullivan traveling troupe as a maid to the lead singer. In 1917, she traveled to Baltimore. She was 26 years old, but still hadn’t finished high school. Huston decided to doctor her records to show she was born in 1901 and erased 10 years from her life in order to complete her education at Morgan College. As the old saying goes, “Black don’t crack”, and Hurston was able to maintain this illusion for the rest of her life without question.

In a letter Hurston wrote to fellow writer Countee Cullen, one wonders if this is how she came to this perspective,

“I have the nerve to walk my own way, however hard, in my search for reality, rather than climb upon the rattling wagon of wishful illusions.”

Hurston seemed to have a firm anchor in reality, while still in pursuit of her dreams, understanding that living life required shoe leather and discipline; her life reflected this.

After Morgan College, Hurston went on to Howard University and earned an associate’s degree. She also co-founded The Hilltop, the renowned school newspaper. In 1925, Hurston received a scholarship to Barnard College and in 1928, only three years later, she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in anthropology.

Being in New York at this particular time allowed Hurston to be a part of the legendary Harlem Renaissance, where she befriended fellow writers Langston Hughes and Cullen.

Boyd wrote:

“Though Hurston rarely drank, fellow writer Sterling Brown recalled, “When Zora was there, she was the party.” Another friend remembered Hurston’s apartment–furnished by donations she solicited from friends–as a spirited “open house” for artists. All this socializing didn’t keep Hurston from her work, though. She would sometimes write in her bedroom while the party went on in the living room.”

By 1935, Hurston had published several short stories and articles, as well as Jonah’s Gourd Vine, her first novel. Mules and Men was her first collection of Black Southern folklore, and her seminal and best known work, Their Eyes Were Watching God, was published in 1937.

In 1938 she published an anthropological work, Tell My Horse, a study of Caribbean Voodoo practices. In 1939 she penned another novel, Moses, Man of the Mountain.

In 1942, Hurston published her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, and was profiled in Who’s Who in America, Current Biography and Twentieth Century Authors. In 1948, she published Seraph on the Suwanee.

While Hurston continued to write and be published, her newer work failed to receive the notoriety it had in the past, and she struggled to support herself as a librarian, and through substitute teaching. In 1959, she suffered a stroke, and was housed in the St. Lucie County Welfare Home. As awareness of Blacks and their plight in the South grew, Zora Neale Hurston and her work slipped into obscurity. The works she produced were truly love letters to an aspect of Southern life, yet somehow they fell out of favor in a time when they should have received greater prominence.

On January 28, 1960, Hurston died at 69 years old. Her neighbors in Fort Pierce, Florida had to take up a collection for her funeral held a week later on February 7. Hurston was buried at the Garden of Heavenly Rest, a segregated cemetery in Fort Pierce. However, the collection wasn’t enough to pay for a headstone, so the grave was left unmarked.

In the Summer of 1973, a young writer named Alice Walker, who would later pen a consequential work of her own, The Color Purple, traveled to Fort Pierce to place a marker on the grave of the author who inspired her own work. Walker found the cemetery, abandoned and overgrown. Walker soldiered on, despite the risk of snakes and poisonous foliage, and soon stumbled upon a sunken rectangular patch of ground that she determined to be Hurston’s grave. Unable to afford the marker she wanted, Walker settled on a plain gray headstone instead. Borrowing from a Jean Toomer poem, she dressed the marker up with a fitting epitaph: “Zora Neale Hurston: A Genius of the South.”

(2/3) In 1973 Walker and Charlotte D. Hunt discovered an unmarked grave they believed to belonged to Hurston. They had it marked as pictured and in 1975 Walker published an article in Ms. Magazine that brought attention to the life and works of Zora Neale Hurston.

PC: Goodreads pic.twitter.com/O9tJqZyKoF

— The Project on the History of Black Writing (@ProjectHBW) February 9, 2021

In 1975, Walker published “In Search of Zora Neale Hurston,” in Ms Magazine, and this is seen as the new launch of Hurston’s storied career.

In 2018, Hurston’s work Barracoon, about a survivor of the Middle Passage, became a bestseller and sold more than 250,000 copies.

Just last year, a collection of Hurston’s early stories was released. Hitting a Straight Lick With a Crooked Stick includes material rarely seen since published nearly a century ago.

The novelist Tayari Jones wrote in the foreword of the collection:

“We can all agree that the end of Hurston’s life was difficult. We can all agree that she deserved her laurels while she still walked among us. Yet Zora, being Zora, did not let mere death end her life.”

As Hurston so aptly said,

Those that don’t got it, can’t show it. Those that got it, can’t hide it.

Sign up for our VIP program to get access to premium content for members only! Use code “OCONNELL” for a discount!