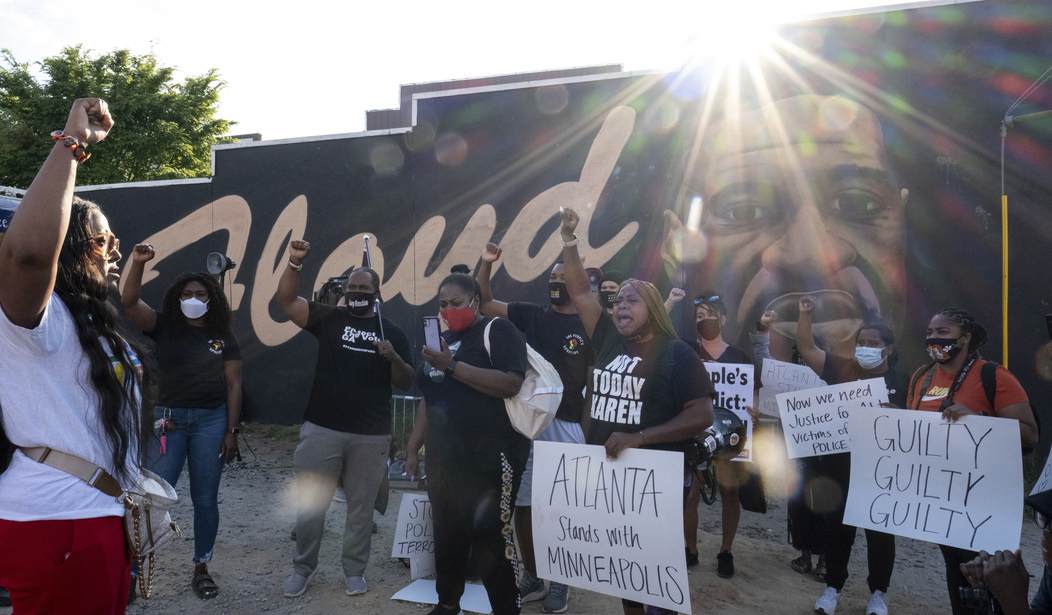

Years after the murder of George Floyd, the Minneapolis Police Department is poised to make changes in how it handles law enforcement. The objective is to create a fairer approach to dealing with crime in the city. To this end, it has entered into an agreement that requires it to make a series of reforms designed to decrease negative interactions between law enforcement and the public, eliminate racial bias, and ensure that justice is served. However, while some of these changes might be positive, there are some that might make it harder for law enforcement to do its job.

Hennepin County District Court Judge Karen Janisch has approved a court-enforceable agreement between the Minnesota Department of Human Rights (MDHR) and the City of Minneapolis. This agreement requires the City and the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) to implement significant changes aimed at addressing race-based policing and strengthening public safety.

The Minnesota Department of Human Rights initiated the investigation following the murder of George Floyd, and the agreement reflects the critical moment in time and the necessary work ahead to address race-based policing.

According to the agreement, multiple entities will hold the City and MPD accountable for implementing the terms of the agreement. A team of independent evaluators will monitor their progress and provide regular reports, while the state court will oversee the agreement and can terminate it once full compliance is reached. The Department of Human Rights will assess whether the City and MPD are satisfying the agreement’s terms.

Additionally, community members and police officers will be involved in the process by providing feedback as MPD develops and updates its policies. The agreement aims to bring about cultural change within the City and MPD, enforce clear policies, and establish accountability, training, engagement, and data collection mechanisms:

The court enforceable agreement requires the City and MPD to set and enforce clear policies that build community trust, provide non-discriminatory public safety, and reduce dangers for officers.

The court enforceable agreement requires the City and MPD, in part, to:

Require officers to de-escalate

Prohibit officers from using force to punish or retaliate

Prohibit the use of certain pretext stops

Ban searches based on alleged smells of cannabis

Prohibit so-called consent searches during pedestrian or vehicle stops

Limit when officers can use force

Limit when and how officers can use chemical irritants and tasers

Ban “excited delirium” training

The court enforceable agreement does not prohibit an officer from relying on reasonable articulable suspicion of criminal activity to enforce the law.

Many have lauded the new agreement, but some community groups have raised concerns. They worry that certain clauses may allow the police union contract to supersede promised reforms, potentially impeding real change:

But as the city and MDHR neared court approval of their settlement agreement, community groups asked the judge not to accept the document without amending details they view as impediments to real reform.

Also considered at the hearing were the concerns of the Twin Cities police watchdog group Communities United Against Police Brutality and government accountability groups Minnesota Coalition on Government Information and the Transparency Institute, which filed amicus briefs weighing in with their analysis of the agreement.

The police watchdog group praised the bulk of the proposed consent decree but sounded an alarm over select clauses that ostensibly permit the police union contract to supersede promises of reforms. These include statements that police disciplinary decisions will be documented and reported only in a way “consistent with any collective bargaining agreements” and that “nothing in this agreement will be interpreted as obligating the city or any unions to violate and/or waive any rights or obligations under the terms of the collective bargaining agreements.

“That means cops can sidestep anything in this consent decree by putting it in their union contract,” group volunteer Andrew Kluis said in June at a community review of the settlement agreement.

Others raised concerns that the settlement agreement could interfere with the state Government Data Practices Act and filed a lawsuit seeking information on police officer coaching. They oppose the agreement’s definition of “discipline” which excludes routine supervision or coaching, which remains unresolved in their lawsuit. The city dismissed the concerns, stating that the agreement must comply with state laws and can be adjusted if needed based on any changes to those laws.

Some of the items on the list are changes I could support, such as banning searches based solely on the “smells of cannabis,” a practice that has been abused frequently by law enforcement officers who pretend they smell weed and use that as a pretext to search someone’s car. I also don’t have an issue with eliminating pretext stops, which occur when an officer pulls an individual over for something like a broken tail light when their true intention is to search the vehicle looking for drugs.

But others, like requiring officers to de-escalate, sound productive, but could be problematic due to the ambiguous nature of the language. Sure, we definitely want law enforcement officers to know how to de-escalate a hairy situation. They should do everything in their power to ensure that violence does not ensue. However, who is to say whether an officer did enough to calm a situation down before resorting to physical force? In a city that is decidedly anti-police, it might make it more difficult for police officers to legitimately handle a situation without placing themselves in danger – especially if it involves a violent suspect.

Limiting when an officer can use force is also a positive change – especially in a city where police are quick to use violence to deal with a situation. But again, this language isn’t very precise, meaning that an officer who used force legitimately might be punished due to subjective opinions on the matter. The city will have to be as detailed as possible when outlining when an officer can use force; otherwise, it could create a negative scenario in which the officer or civilian is unnecessarily harmed.

All in all, if a police department recognizes the need to change, then it should change. I will never pretend our justice system is perfect – it’s far from it. However, when making these changes, they must be careful not to hinder officers from targeting actual criminals.