RedState has highlighted many noteworthy people so far during February’s Black History Month, like singer Billie Holiday, ‘Stagecoach’ Mary Fields, entertainer Korla Pandit, actor/comedian Bill Cosby, and the Fisk Jubilee Singers (you can find the full list here).

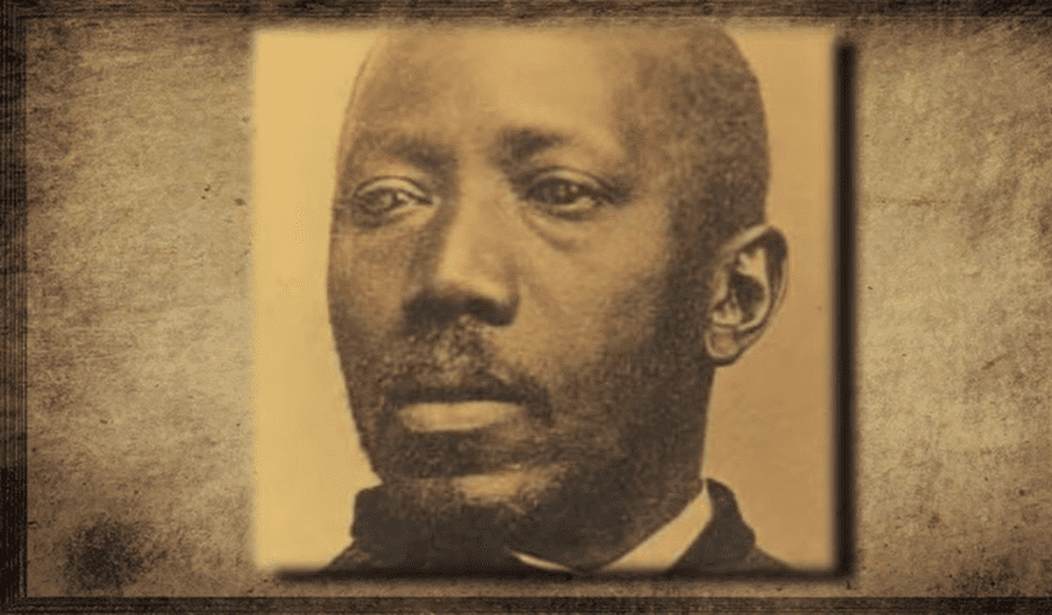

Another remarkable life full of achievements we can be guided by is that of Martin Robison Delany. His journey led to him becoming the first Black field officer in the U.S. Army and a doctor, among other things.

His was a great example of someone who simply refused to give up on his pursuit of a better life for himself and his fellow Americans.

But that pursuit began with his own quest… to be allowed to get an education at all. You see, his mother was free but his father was a slave, and where he was born on May 6, 1812, and grew up — Charles Town, Virginia (which would later become part of West Virginia) — families like his teaching their children to read and write wasn’t exactly legal. So, Delany’s mother took the brood to Pennsylvania.

But since they had moved to a small town, higher education was limited, so he decided to walk the 130 miles to Pittsburgh at age 19. The site Civil War Pittsburgh picks up the story from there.

His experiences in the bustling city at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers helped shape Delany’s voice within the abolitionist community, including Delany’s founding of The Mystery – the first African American-operated newspaper west of the Allegheny Mountains. This, of course, preceded Delany’s work with Frederick Douglass on the North Star in 1847.

It was also in Pittsburgh that Delany began his lifelong work as an abolitionist and activist.

As this video compiled by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette points out,

“He was a dreamer. He had a fantastically ambitious dream, and he came so close to realizing that dream. It was within his reach but then, the dream was crushed.

…

In 1850, Martin applied to Harvard Medical College. He was 38 years old, with an impressive list of accomplishments.”

He, along with two other students, were the first Black people admitted to the school. However, during the first semester, a group of white students protested, and he was forced to leave.

But his dream of becoming a doctor was only crushed temporarily. He was later able to apprentice with physicians.

Turning to his writing, some of Delany’s lyrical prose is captured in this brief reading from his journals, which was culled from traveling across the country, including to Canada. (In the video at the end of this article, you’ll hear an actor playing Abraham Lincoln refer to Delany as being Canadian. It’s possible he gained citizenship there, at one point.)

Part of the reason for his exploration stemmed from a major slave revolt that took place in Cuba in the 1840s. He decided that Black people would never be fully accepted as equals in the United States, so he hoped to inspired people to found a new nation elsewhere that would.

One facet of his writing that intrigues me is his detour into fiction. He wrote a novel about a fictional slave insurrection, “Blake; or the Huts of America.”

The book’s real-life origins were described by the Encyclopedia Virginia:

Blake responds specifically to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which made it illegal for any free person living in a free or slave state to aid an escaped slave seeking freedom, and to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), which stripped all blacks living in the United States—enslaved and free—of any citizenship rights.

It added that he was also inspired by the Cuban slave riots of the previous decade. In Blake, Delany seemed to seek to create a myth, a folk hero tale. The story was written, then published in serial form from 1859 to 1861 in weekly magazines, while he tried to have it published in book form. But he failed to find a publisher. And since the novel is incomplete (the final, six weeks worth of serials were lost), a fragment of it was published in 1970.

Delany still felt unsatisfied by the explorations he had done in our hemisphere to find a place for Black people to live freely. So, he set off to Africa to look there. But then, the Civil War broke out, and he returned to the U.S. to help recruit Black soldiers. It’s thought that he convinced thousands to sign-up to fight for their freedom on the Union side.

Then in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all slaves in the rebel states, and in any area of the South where the Union had regained control. And it appears Lincoln heard about this ambitious man from Pittsburgh and his efforts. So, he met with Delany. Soon afterwards, Delany was commissioned a Major — making him the highest-ranking Black soldier up to that point in the Army.

I can’t think of a more fitting tribute to Delany than this.

According to the inscription on a historical marker in Jefferson County, West Virginia, here are details on what the two men discussed, then what Lincoln did on February 8, 1865, just after that remarkable, face-to-face meeting:

During the Civil War, Delany met with President Abraham Lincoln. Delany told President Lincoln of his plan to recruit black troops commanded by black officers to go south and fight. President Lincoln accepted this plan and sent a note to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton advising Stanton to meet with Delany.

“Do not fail to have an interview with this most extraordinary and intelligent black man.” A. Lincoln

Then after the war ended, he spent time in South Carolina, training former slaves to be self-sufficient, stressing the need to own their own land to farm.

Later on, as this entry from the Biography Channel website on Delany shows, he started to dip his toe into electoral politics…as a Republican:

After the war, Delany tried to enter politics. A quasi-biography, written pseudonymously by a female journalist under the name Frank A. Rollin—Life and Services of Martin R. Delany (1868)—was a stepping stone to serving on the Republican State Executive Committee and running for lieutenant governor of South Carolina.

The entry added that though he never ended up getting elected to an office, “he was appointed a trial judge.”

His politics did lean to the radical side at times, with his work in seeking out a Black homeland considered a major milestone in the history of black nationalism. Perhaps it’s not surprising that in his own time, he was considered as something of a pariah, even among his fellow abolitionists. But when someone ekes out a trail to freedom in other ways for thousands of people, it’s worth side-stepping some aspect of their personal politics. Because some things are bigger than politics.

And though we can’t know exactly what happened in the meeting between Delany and Lincoln, you’d have to think it might have been something like this excellent reenactment below, via the History’s Flipside YouTube channel.

One line from it that especially rings true is the one about why he was so passionate about the idea of raising “40,000” new recruits to march through the South — commanded by Black commanders. He saw it as a way to overcome something he had personally been affected by: the prohibition against Blacks being taught to read and write. As the actor playing Delany points out to the Lincoln actor, many weren’t able to read his Emancipation Proclamation.

Enjoy!

Join the conversation as a VIP Member