I’ve encountered many interesting people during my writing years – people like Joseph Heller, Soichiro Honda, Whitey Ford, Mike Mansfield, and Ross Perot.

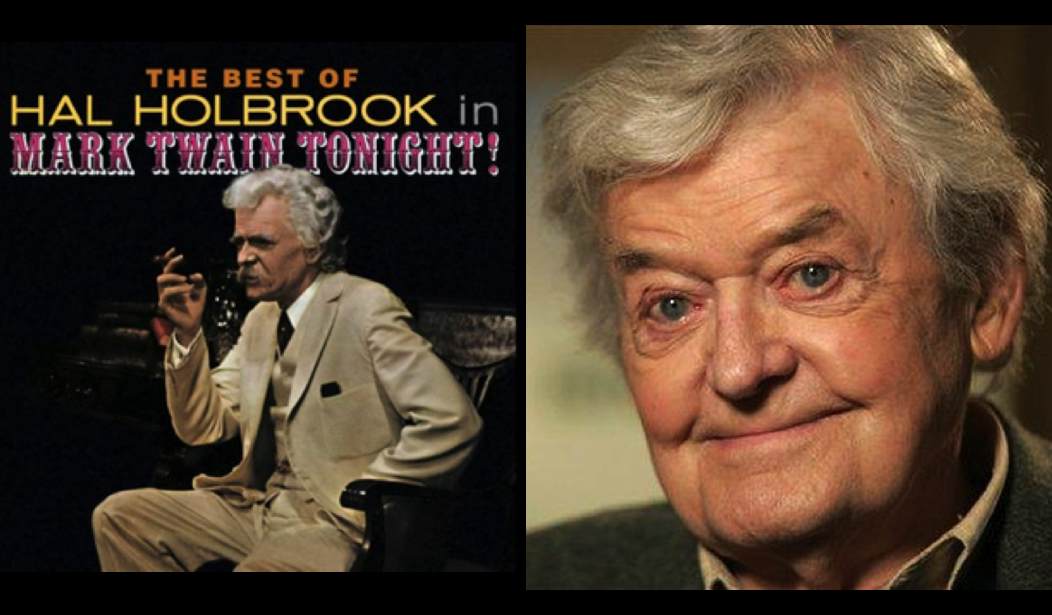

But the one who likely left the most lasting impression on me was Hal Holbrook, the actor. He did Broadway, movies, TV, even soaps. He was best-known for decades of becoming Mark Twain, alone, on-stage.

He taught me so much about art and acting in one day that I’ve savored and drawn on the lessons now for more than 60 years.

I was a teenager, editor of the student paper at the prep school we both attended, though 20 years apart. He was returning to campus that weekend with his now legendary one-man stage performance “Mark Twain Tonight.”

Holbrook performed his show thousands of times around the world for 60 years, longer than the real Mark Twain was on stage. Holbrook died two years ago at 96, 21 years longer in life than Twain.

I scheduled a short interview with Holbrook the day of his performance in the school auditorium, a Saturday, as I recall. What began with routine questions in the school’s guest house turned into countless inquiries about his life, his Army and life experiences, his acting, his act and about art as an important, integral part of life. I would use his lessons countless times in my own writing.

Holbrook was so open, approachable, and generous with his time. I was mesmerized, no, actually magnetized by him and his thoughts. We strolled the campus while he recalled life there. He listened well and responded to every question.

I wanted to talk about Samuel Clemens or Mark Twain, Huckleberry Finn, and Tom Sawyer whose 19th century tales of teenage misadventure and mischief in rural Missouri had captivated so many of my youthful reading hours.

They had struck a similar chord with Holbrook as a college drama student. Until Twain’s writing, America’s fiction had largely mirrored the British drawing-room tales that TV has now turned into dramatic serials.

Twain’s writing changed everything. It was realistic, vernacular, full of dialect and common-man slang. It was so real and true to that antiquated time that a century later, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” and Tom Sawyer were banned in some overly-sensitive places.

Holbrook memorized reams of Twain stories, letters, and enduring quotes. They sounded just as sharp as they had in the 19th century:

Suppose you were an idiot. And suppose you were a member of Congress. But I repeat myself.

I did not attend his funeral, but I sent a nice letter saying I approved of it.

God created war so that Americans would learn geography.

Holbrook answered my questions directly. He looked straight at me like I was important. He listened closely and patiently, not something a naive teen always got from accomplished adults.

Were his performances scripted? No. He recounted Twain's stories and quotes as they came to mind. That, Holbrook paused to emphasize, made them and him more spontaneous on stage. He never wanted to appear to be acting.

“The stage isn’t a book,” Holbrook said, “where you tell readers everything. It’s a place where you lead the audience to discover for themselves what you’re presenting. Or at least they think they discover it.”

What was to have been a brief, polite student interview had become a daylong tutorial on drama and his craft. Holbrook said he tried to stick close to the author’s style and voice and recalled another Twain quote:

The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter. Tis the difference between the lightning bug and lightning.

As the afternoon wore on, we ambled toward the theater basement where he began the long, methodical process of turning himself into an old man. “The older I get,” Holbrook said, “the less I have to do.”

The bare bulbs of the makeup mirror bleached his face as the stage lights would upstairs. So, he sponge-darkened his face and hands with makeup. The eyebrows grew bushy. And there was that marvelously massive mustache.

Age lines drawn in around the eyes. “Wrinkles should merely indicate where the smiles have been.” That sounds like Twain, I said. The man who was becoming Twain created some smile-wrinkles.

The actor had said you can’t tell people from the stage, ‘Hey, look how old I am.’ You just show it, let them reach their own conclusion.

I was fascinated at the detailed transformation going on before my eyes. All the time I asked questions. Why this? Why that? And he answered.

Until, that is, he pulled out a makeup pen and held up his hand for silence. He proceeded methodically to add age spots on one check and then the other. He was counting them – 74 on the left, then 74 on the right. When he finished, I said no one in the audience could see the spots, let alone know how many.

Holbrook leaned into my face. “But I know!” he said, “Minor details are not minor.”

Then came the 19th century white-linen suit with the old leather suspenders that Holbrook wore for authenticity but the audience would never see. And then a wig with the famous unruly white hair flying about.

That did it for me. This was the man who had written the books I had consumed as a boy, the fictional characters all based on real people who became my mental companions – Huck, Tom Sawyer, his crush Becky Thatcher, Aunt Polly, the feuding Grangerfords and Shepherdsons, and, of course, the massive river that still flows through life there.

Into Twain’s vest pocket went three cigars. “I don’t know if Twain smoked onstage,” admitted the man formerly known as Holbrook, “But I like the idea.” Holbrook, I suddenly realized, was now speaking in the gravely voice of an old man.

Into the vest went another minor detail, an antique penknife that Holbrook’s grandfather had used to snip the end of each cigar before lighting it with a stick match. The audience would never know that either.

Holbrook stood up, held out his arms, silently seeking the awed teen’s approval. He got it.

Soon after, from my theater seat, I witnessed an old man onstage who bore no resemblance to the man I’d conversed with all afternoon. Shuffling about, like someone certifying each step before taking it, he told stories that made the audience chuckle and laugh and nod knowingly.

“Truth is stranger than fiction,” he said, puffing on a cigar, “but that’s because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities. Truth isn't.”

At one point well into the evening, the elderly author had to rest in an old chair. He put down his cigar, crossed his legs with effort, sighed, and fell silent.

So did the audience. He remained silent. So did the audience, puzzled. Waiting. For a long time. Uncomfortably.

Then, one by one, audience members began to discover for themselves that the old guy on stage had fallen asleep right in front of them. The laughter spread, grew louder, and finally woke him.

“I do not fear death,” Twain noted. “I had been dead for billions and billions of years before I was born, and had not suffered the slightest inconvenience from it.”

Some years later after that amazing day, I could no longer resist seeing for myself the place that had inhabited my imagination for so long, St. Petersburg in the books, Hannibal, Mo. in reality.

“You don't know about the adventures of Huckleberry Finn without you have read a book of that name by a man named Mr. Mark Twain. He told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth. But that ain't no matter.”

When I read that opening of ‘The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’, I was hooked. The people talked like real people. The young boy told the entire tale himself. It occurred in an innocent era when the worst thing a boy could do was tell a lie or smoke a corncob pipe, and scolding aunts led miscreants away by the ear.

One-hundred miles north of St. Louis, Hannibal is still a rural Missouri community tied to agriculture and commercially proud of its literary history that brings in thousands of visitors from around the world and millions of dollars.

Hannibal tries mightily to live up to its fictional reputation with local events and some spots even renamed to match ones in the books. Samuel Clemens grew up there, the son of a circuit-riding judge caught in a rainstorm on his horse and died soon after of pneumonia.

While there, I heard a story, and that afternoon drove a few miles west of town to see. There on the roadside, beneath the towering cedars of the old Big Creek Cemetery, lies enduring evidence of Mark Twain’s impact 139 years after the first book’s publication.

A granite headstone marks the resting place of Laura Hawkins, who was a pretty little girl when she lived across the street from and first caught the eye of a little boy named Sam Clemens. Many years later Clemens confided a secret to his childhood playmate. It was a secret she could not keep in death.

And so Laura Hawkins' gravestone carries two names. One is Laura Hawkins, who died in 1928. The other is Becky Thatcher, a pretty little girl granted eternal life by her childhood pal.

Minor details are not minor.

------

This is the ninth in an occasional series of Memories that RedState editors suggested. The others are linked below. Feel free to share your relevant memories on today's post in the Comments below, as many others have shared their Memories. I hope you enjoyed this and will pass it on to others. Follow me @AHMalcolm

PREVIOUS MEMORIES:

Join the conversation as a VIP Member